Among the Quadi, on the river Gran

I hate no one, love no one, am no one,

My armor hollow, crumpled, a tumbling can

Among the Quadi, on the river Gran.

River awash with bodies, rinse my hand.

I neither love nor hate what it has done.

Among the Quadi, on the river Gran

I neither love nor hate what I’ve become.

I neither love nor hate what I’ve become

Among the Quadi, on the river Gran

Slaughtering boys with long hair spun of sun.

I neither love nor hate what I have done

Galloping after stragglers on the run.

Rinse, rinse my hand, as only a river can.

I love no one, hate no one, am no one

Among the Quadi, on the river Gran.

*****

This poem originally appeared in The Classical Outlook, Vol. 97, No. 3

Amit Majmudar writes: “I am a fan of Marcus Aurelius, and I wrote this little poem around the same time I wrote an essay about harmonics between the Meditations and the Bhagavad-Gita, which I published my translation of in 2018.

Yet the original idea—a triolet that plays with that oddly pentametric subtitle of one of the chapters of the Meditations—occurred to me years ago. I am pretty sure I wrote, or tried to write, a triolet with this refrain maybe fifteen years ago. I lost it, never sent it out, one of the literally hundreds of poems I write but never send out. (Creatively I am like a fish, laying a superabundance of eggs, expecting only a small percentage to survive.)

When I reread the Meditations recently, getting my thoughts together for the essay, I saw that subtitle and had the same idea a second time, or remembered having had the idea (and hence inadvertently had it again). These two triolets are my attempts at reconstructing a poem I wrote and forgot years ago. I could not recall if I had made “Among the Quadi, on the river Gran” the first or second line of that ur-triolet. So I blundered around and found my way into this “double triolet.”

The image of Marcus Aurelius as a reluctant Stoic warlord is irresistible to me. I think the best commentary on this poem is the essay I wrote at the same time, published over at Marginalia at the Los Angeles Review of Books. This is the link to that essay:

https://themarginaliareview.com/the-gita-according-to-marcus-aurelius/“

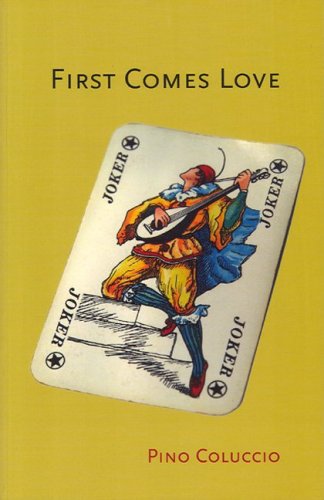

Amit Majmudar is a poet, novelist, essayist, translator, and the former first Poet Laureate of Ohio. He works as a diagnostic and nuclear radiologist and lives in Westerville, Ohio, with his wife and three children.

Majmudar’s poetry collections include 0’, 0’ (Northwestern, 2009), shortlisted for the Norma Faber First Book Award, and Heaven and Earth (2011, Storyline Press), which won the Donald Justice Prize, selected by A. E. Stallings. These volumes were followed by Dothead (Knopf, 2016) and What He Did in Solitary (Knopf, 2020). His poems have won the Pushcart Prize and have appeared in the Norton Introduction to Literature, The New Yorker, and numerous Best American Poetry anthologies as well as journals and magazines across the United States, UK, India, and Australia. Majmudar also edited, at Knopf’s invitation, a political poetry anthology entitled Resistance, Rebellion, Life: 50 Poems Now.

Majmudar’s essays have appeared in The Best American Essays 2018, the New York Times, and the Times of India, among several other publications. His forthcoming collection of essays, focusing on Indian religious philosophy, history, and mythology, is Black Avatar and Other Essays (Acre Books, 2023). Twin A: A Life (Slant Books, 2023) is the title of a forthcoming memoir, in prose and verse, about his son’s struggle with congenital heart disease.

Majmudar’s work as a novelist includes two works of historical fiction centered around the 1947 Partition of India, Partitions (Holt/Metropolitan, 2011) and The Map and the Scissors (HarperCollins India, 2022). His first children’s book also focuses on Indian history and is entitled Heroes the Colour of Dust (Puffin India, 2022). Majmudar has also penned a tragicomic, magical realist fable of Indian soldiers during World War I, Soar (Penguin India, 2020). The Abundance (Holt/Metropolitan, 2013), by contrast, is a work of contemporary realism exploring Indian-American life. Majmudar’s long-form fiction has garnered rave reviews from NPR’s All Things Considered, the Wall Street Journal, Good Housekeeping, and The Economist, as well as starred reviews from Kirkus and Booklist; his short fiction won a 2017 O. Henry Prize.

Majmudar’s work in Hindu mythology includes a polyphonic Ramayana retelling, Sitayana (Penguin India, 2019), and The Mahabharata Trilogy (Penguin India, 2023). His work as a translator includes Godsong: A Verse Translation of the Bhagavad-Gita, with Commentary (Knopf, 2018).

Photo: “File:0 Marcus Aurelius Exedra – Palazzo dei Conservatori – Musei Capitolini (1).jpg” by Unknown artist is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.