Tell me the star from which she fell,

Oh! name the flower

From out whose wild and perfumed bell

At witching hour,

Sprang forth this fair and fairy maiden

Like a bee with honey laden.

They say that those sweet lips of thine

Breathe not to speak:

Thy very ears that seem so fine

No sound can seek,

And yet thy face beams with emotion,

Restless as the waves of the ocean.

‘Tis well. Thy face and form agree,

And both are fair.

I would not that this child should be

As others are:

I love to mark her indecision,

Smiling with seraphic vision

At our poor gifts of vulgar sense

That cannot stain

Nor mar her mystic innocence,

Nor cloud her brain

With all the dreams of worldly folly,

And its creature melancholy.

To thee I dedicate these lines,

Yet read them not.

Cursed be the art e’er refines

Thy natural lot:

Read the bright stars and read the flowers,

And hold converse with the bowers.

*****

This poem for a mute girl and another (‘To a Maiden Sleeping After her First Ball’) can be found in All Poetry; they each have an accurate but uninspiring AI-driven analysis after them; the subsequent comments are more engaging:

WolfSpirit – “keep writing, Benjamin. you may just be a known poet someday.  “

“

Linda Marshall – “I know Disraeli as a novelist and (of course) as a politician.

This is the first poem of his I’ve ever read!

It has its moments and of course tastes were different in those days but there are rhythmical infelicities and some rhymes that verge on the comic.

I can see why he’s known for his prose rather than his poetry!”

Benjamin Disraeli was born into a Jewish family in 1804; his father quarrelled with the synagogue and renounced Judaism, and had all the children baptised into the Church of England when Disraeli was 12. After school, Disraeli was articled to a law firm at age 16, and his career went from there to stock market speculation, financial ruin, novel writing, and then politics. He was twice Prime Minister of the United Kindom, and was appointed Earl of Beaconsfield by Queen Victoria in 1876. He died in 1881, unmourned as a poet.

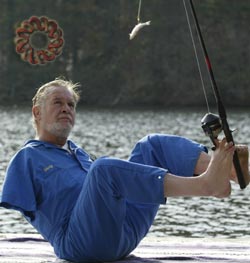

Photo: Earl of Beaconsfield, K.G. Photographed at Osborne by Command of H.M. The Queen, July 22, 1878. This file was derived from: Benjamin Disraeli CDV by Cornelius Jabez Hughes, 1878.jpg