Once a devious queen lodged just one tiny pea

Under twenty soft mattresses, wanting to see

Out of many young princesses which was the one

Who deserved to be matched with the prince, her fine son.

For she knew a true princess was dainty and fine,

And that little legume underneath the frail spine

Would prevent her enjoying the tiniest rest,

And by this all would know she had passed the queen’s test.

But you see, a true princess is also polite,

So when, bleary-eyed after a long, sleepless night,

Each was asked how she’d slept by the queen the next day,

She replied, “Very well,” and was sent on her way,

Till one morning a girl hollered, “What is this lump?

Do you call this a bed? Who can sleep in this dump?”

So the queen said okay. The prince married her straight.

And the moral is: don’t let your mom choose your mate.

*****

Max Gutmann writes: “It always frustrated me that the fairy tale couldn’t seem to see the flaw in the queen’s thinking.”

This poem was first published in Snakeskin.

Max Gutmann has contributed to New Statesman, Able Muse, Cricket, and other publications. His plays have appeared throughout the U.S. (see maxgutmann.com). His book There Was a Young Girl from Verona sold several copies.

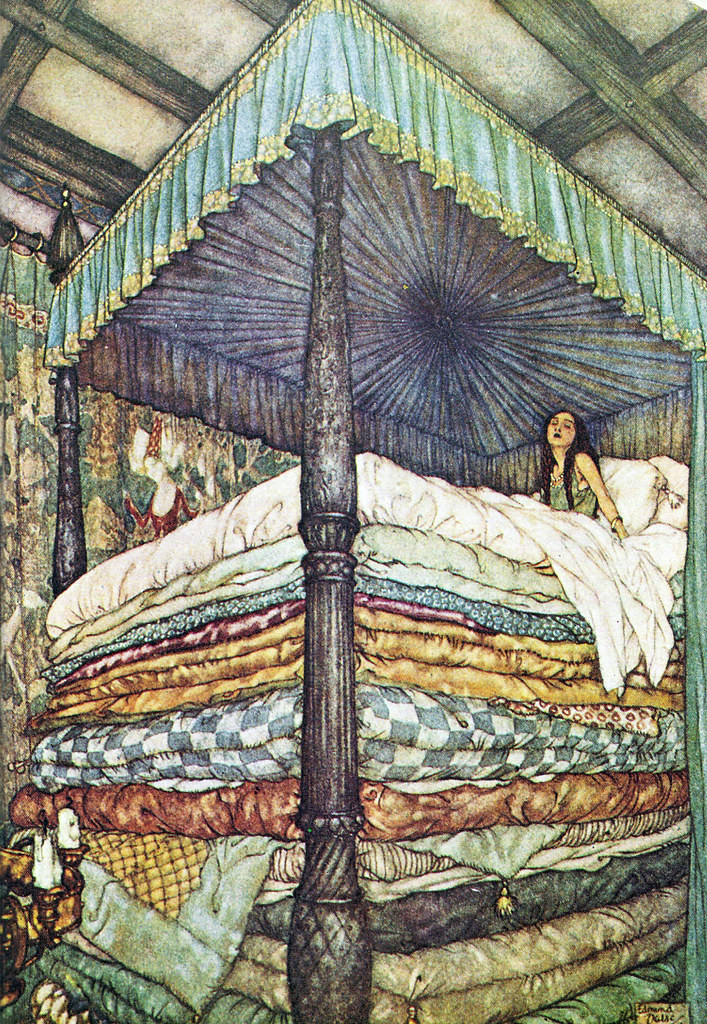

Illustration: ‘The Princess and the Pea’ by Edmund Dulac. Dulac illustrated several of H.C. Andersen’s fairy tales, many of which include sarcastic social commentary on pretentiousness.