Notes left behind by strangers long since dead

entranced my mother—not the squiggles, dots

and lines themselves, but what musicians read

from them on radio, the sounds ink spots

had spelled. In quartets and in Claire de lune,

her young ears heard what many can’t discern:

enchanting, complex things—beyond the tune—

about which she had little chance to learn.

When she grew up, her voice was warm and rich

as those of many singers who’d been schooled

in breath control and quarter notes and pitch.

She was as musical as some who’ve ruled

the concert stage—but she sang in the car

and kitchen; we heard her wide repertoire.

We heard her car and kitchen repertoire

of opera arias, concerto themes,

and deep regret she never got as far

as piano lessons. Her childhood daydreams

were seeded by the sagging upright housed

at her Aunt Margaret’s—maybe she’d learn there?—

and fed by radio: Puccini roused

her love of opera, Brahms made her aware

of string-sung drama. She pursued her chances

to learn and listen—and also to plead

for lessons, though her parents’ circumstances

made that impossible. But she’d succeed

in giving her kids what she’d never had—

assisted in that effort by my dad.

It took substantial effort. Mom and Dad

lacked wealth, but not love or imagination.

Wrong turns became adventures, plans gone bad

would show up later in a wry narration.

Fun for us kids was low-cost, even free:

a paper crown on birthdays, or a game

made out of raking leaves, or a decree

that it was Ice Cream Tuesday. We became

as skilled as they were at composing joy:

we heard another music in our days

of sibling harmony, learned to deploy

exuberance and laughter as one plays

an instrument. And then catastrophe

and cleverness brought opportunity.

Our clever dad saw opportunity

when fire destroyed a nearby school, with all

its contents lost—including, doubtlessly,

the old piano. But Dad made a call

and had the badly damaged upright brought

to our garage. It was a rescue mission:

the smoky wreck could be revived, he thought.

He’d never played, and he had no ambition

to do so, but he always had been good

at fixing things. And so he scrubbed the keys,

patched felts and hammers, and restored the wood

of the disfigured case. And by degrees,

the sooty hulk became something we prized.

Untrained, unmusical, he’d improvised.

With talents of his own, he’d improvised,

so we could, too. And he and Mom had planned

and saved so we’d have lessons. Though advised

to start us at age seven, Mom had grand

ambitions for my younger hands. At six,

I got to know the keys and clefs with smart,

no-nonsense Mrs. Steffen, who would mix

high standards and commitment to the art

of making music with kid-friendly stuff.

I played a little Mozart (simplified),

a piece called “Crunchy Flakes” and other fluff,

some basic boogie-woogie, drills that tried

my patience. And my two sisters and I

all played—too loudly—Brahms’s lullaby.

We all played Brahms’s famous lullaby,

and argued over which of us would get

to practice next; I knew the time would fly

when it was my hour. Paired in a duet,

two sisters often bickered just as much

as we made music, but we learned to work

together, synchronize tempo and touch,

forget the other could be such a jerk.

Years later I made music my profession,

and it became both job and joy, a route

to self-sufficiency and self-expression—

a gift whose worth I never could compute,

from parents who would never read a score,

but who would give us music and much more.

They gave us music, but a great deal more

than just the audible variety.

Their well-tuned lives—examples set before

us kids—were also music. They taught me

to practice patience in both work and play;

to face discord and my mistakes with poise;

to transpose trouble to keys far away;

to find and share the song within the noise.

My mother’s dreams, my father’s diligence,

and love composed a priceless education.

And those gifts all enrich the resonance

I hear in Bach and Brahms—in my translation

of small black symbols in the scores I’ve read:

notes left behind by strangers long since dead.

*****

Jean L. Kreiling writes: “I often find myself reminding readers that poems are not always autobiographical—but ‘Another Music’ is thoroughly autobiographical, and it’s meant to honor my devoted and fun-loving parents. My mother’s love of music and my father’s brilliance did shape much of my life, and my parents gave me (and my siblings) a richly happy and secure childhood. My parents’ legacy has lived on in the lives of all of their children: music has been important in all our lives, and family has been a top priority and a joy for all of us. Mom and Dad supported my work as a poet just as enthusiastically as they supported my musical endeavors, and I’m grateful that they both lived to see my first book of poems published.”

‘Another Music’, a seven-sonnet crown, was originally published on Talk to Me in Long Lines.

Jean L. Kreiling is the author of four collections of poetry; her work has been awarded the Able Muse Book Award, the Frost Farm Prize, the Rhina Espaillat Poetry Prize, and the Kim Bridgford Memorial Sonnet Prize, among other honors. A Professor Emeritus of Music at Bridgewater State University, she has published articles on the intersections between music and literature in numerous academic journals.

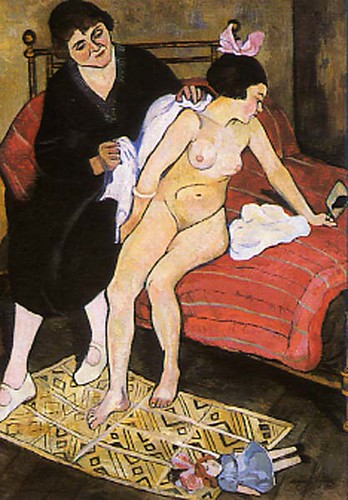

Photo: “~ Play with me… ~” by ViaMoi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.