The hyperspace viewer shows a flowing plane

of treebark, roots; a distorted approximation

of what we aren’t permitted to see. Clearing again

with each rugose transformation,

limited by the speed of post-quantum rendering,

the map of our passage grows:

an icebound dimensional lake thaws, remembering

the hot pulse of its creation, shows

palpable vestiges of times, energies and matters

through which our wake will trace.

The reflection of our ship shimmers, spatters

light back to streaming stars. We race

onward, out to where no atmospheres and skies

of planets can frustrate our vision;

the provocation of empty black where no suns rise

unbearable without acquisition.

Particular silence surrounds us like a felt of absence,

itself the sinuous, tentacular touch

of a void-god whose cult is abstinence,

who meditates on dark too much—

those distances between the stars and galaxies—

and has a singular affection

for black holes and cosmic fallacies.…

Sometimes we overreach. Each direction

(up? down? sideways?) seems different now;

our ship’s brain’s blocked—no ability

to calculate location. We tell it to go back: how—

why these results? We’ve lost mobility,

it says; the only options are charm and strange.

We clear its cache, then re-install the route.

On the viewscreen, no known space in range;

nothing but the false stars of snow. About

fifty-six hours in, the background gigahertz hiss

of relic radiation is finally broken:

our A.I. transmits a mad-dog growl. Something’s amiss.

What does it mean? Unspoken

fears flicker on our faces like shadows cast

by entities we feel but cannot see,

leaving invisible tracks across the vast

cosmic chasm, preceding one more tangibly

manifesting. A small silver embryo afloat

in amnion of atrament, our ship

is dwarfed by tentacles of terror. We’re but a mote

in the eye of a demonic god, a blip

cascading down through superimposed dimensions

to our doom, where something pines

beyond a threshold, longs to enter our attention—

and hungers for the taste of human minds.

Our Earth’s a pale blue memory, a ripe prize

to harvest; our civilization will revert

to a predawn whence no human can ever rise.

The God Void sits in judgment—but won’t convert

one soul. Its vastness grows, membranous and bloody,

slithers back into the open portal of a queer

dwelling where it withdraws to sleep and let the muddy

waters of vacuum clear.

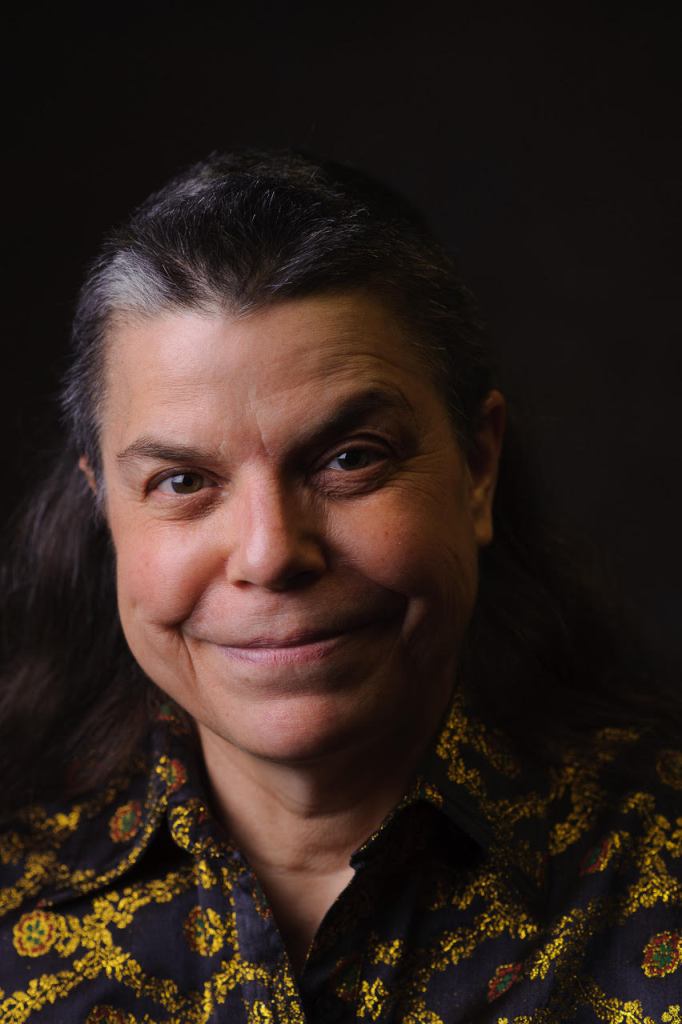

F. J. Bergmann writes: ” ‘Further’ first appeared in the Lovecraft eZine. I selected ‘Further’ because I’m fond of cosmic horror, and I was pleased with being able to maintain the form and narrative at this length. The process I used for this poem is what I call ‘transmogrification’: starting with a text source, which can be anything, from another poem to spam, I write a different poem or story using most or all of the words from the source, generally in reverse order. The source for this poem was ‘Let Muddy Water Sit and It Grows Clear,’ a considerably shorter nature poem by Ted Mathys, whose title is reflected in the last two lines of my poem.”

F. J. Bergmann is the poetry editor of Mobius: The Journal of Social Change (mobiusmagazine.com), past editor of Star*Line, the journal of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Poetry Association (sfpoetry.com), managing editor of MadHat Press (madhat-press.com), poetry editor for Weird House Press (weirdhousepress.com), and freelances as a copy editor and book designer. She lives in Wisconsin with a husband, intermittent daughters and a horse or two, and imagines tragedies on or near exoplanets. Her writing awards include SFPA Rhysling Awards for both long and short poems and SFPA Elgin Awards for two recent chapbooks: Out of the Black Forest (Centennial Press, 2012), a collection of conflated fairy tales, and A Catalogue of the Further Suns, first-contact reports from interstellar expeditions, winner of the 2017 Gold Line Press manuscript competition. She was a 2019 quarter-winner for Writers of the Future. Venues where her poems have appeared include Asimov’s SF, Missouri Review, Polu Texni, Spectral Realms and Vastarien; her speculative fiction has been published in Abyss & Apex, Little Blue Marble (CA), Pulp Literature (CA), Soft Cartel, WriteAhead/The Future Looms (UK), and elsewhere. She has competed at National Poetry Slam with the Madison Urban Spoken Word slam team. While she has no academic literary qualifications,. she is kind to those so encumbered. In a past life, she worked with horses. She thinks imagination can compensate for anything.

Contact F. J. Bergmann: demiurge@fibitz.com