It ran up the flagpole

To not one salute.

No win-win was won,

We ate no low-hung fruit.

The long view was taken,

We kicked every tyre.

No needles were moved

As we sang to the choir.

There wasn’t the bandwidth

To see this one through.

Would the paradigm shift?

We just hadn’t a clue.

Our cutting-edge plan

To abolish cliché

From the meetings we’re forced

To endure every day

In the final analysis

Found no defender,

So we took a step back

And right-sized the agenda.

*****

Stephen Gold writes: “I didn’t have any deep philosophical reasons for writing it. It’s just a wry dig at corporate crapspeak and how often very bright people find it irresistible.”

Stephen Gold was born in Glasgow, Scotland, and practiced law there for almost forty years, robustly challenging the notion that practice makes perfect. He and his wife, Ruth, now live in London, close by their disbelieving children and grandchildren. His special loves (at least, the ones he’s prepared to reveal) are the limerick and the parody. He has over 700 limericks published in OEDILF.com, the project to define by limerick every word in the Oxford English Dictionary, and is a regular contributor to Light and Lighten Up Online (where this poem was first published).

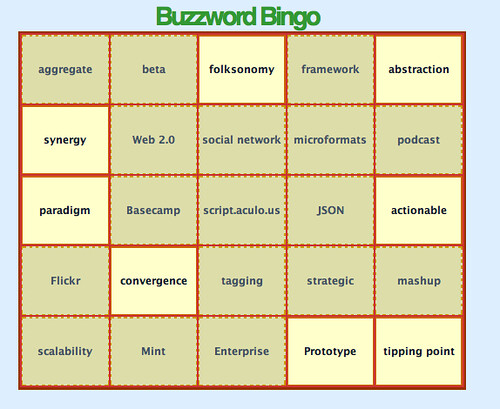

“Buzzword Bingo” by Zach ‘Pie’ Inglis is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.