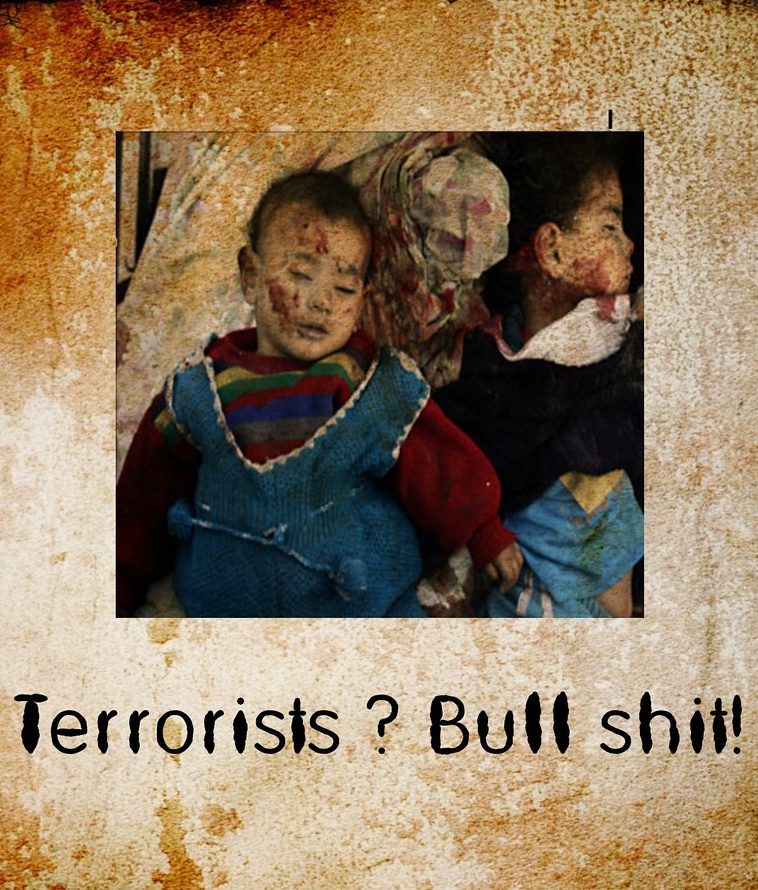

Leo Yankevich: ‘The Terrorist’

Only six, she stands before a tank,

looking at its armour, while inside

soldiers heed orders from a higher rank.

There isn’t any place for her to hide,

no door to head for, no abandoned car

to slide beneath. Pure terror rules her land.

When finally crushed, she rises past the star

of David, with a stone clutched in her hand.

Janet Kenny: ‘Didn’t They Know?’

(In memory of a lost poem by Robert Mezey)

Didn’t they know that when they swarmed

and slashed and slaughtered what they saw

as an oppressor’s nest, the rage

that they aroused would turn and pour

with molten heat back on their house?

Their captive children now must pay,

small targets in a concrete cage.

No treaty, pact, no peace no truce.

Didn’t they know? Didn’t they know?

No map to show another way.

Olive farmers pay for crimes

of other nations, other times.

No mercy here, no one is just.

Two agonies, two brains concussed.

Nothing to see here. False alarm.

Police not needed to disarm

two weeping peoples each aware

that no solution slumbers there.

Hearth and cradle now makes clear

an ancient poem brought them here.

Where is the psalm that both can share?

Where is the psalm that both can share?

Robin Helweg-Larsen: ‘Both Sides Justify Their Terrorism’

When pleas for justice are of no avail,

when governments praise death and theft,

and courts say you’re in error;

when the UN is blocked to fail,

the only recourse left

is terror.

When no one cares that Yahweh willed

that Jews alone should have this land

(and God’s never in error)

and prior residents must be killed,

yet they won’t leave, they force your hand:

to terror.

Gail Foster: ‘On The Occasion of Benjamin Netanyahu Quoting Dylan Thomas’

Don’t tell me that you fight a righteous fight

How many children have you killed today

I’ll give you rage. I’ll give you rage alright

Your anger and your ego burning bright

Are razing all that’s standing in your way

Don’t tell me that you fight a righteous fight

How many have you sent into the light

Before they even had the time to pray

I’ll give you rage. I’ll give you rage alright

How many have you saved or sent in spite

Up to the sky in ashen clouds of grey

Don’t tell me that you fight a righteous fight

In clouds as those who in the fog and night

Were put in trains and disappeared away

I’ll give you rage. I’ll give you rage alright

You speak as if your soul was white as white

Yet deep inside you darkness holds its sway

Don’t tell me that you fight a righteous fight

I’ll give you rage. I’ll give you rage alright

Tom Vaughan: ‘The Land’

Let’s pretend that the war

could be over, and peace

reigned even if only

this evening. O please

pick up your anger

and soak it with mine

in six large barrels

of miracle wine

and then let us dance

like lovers, as though

this land’s many meanings

didn’t all signal no

and we could make ploughshares

out of our swords

and translate the past

into one shared world

and even if dawn

will scatter the night

and send us both stumbling

into the light

where smooth olives glisten

in the warm sun

like belts of bright bullets

ripe for a gun.

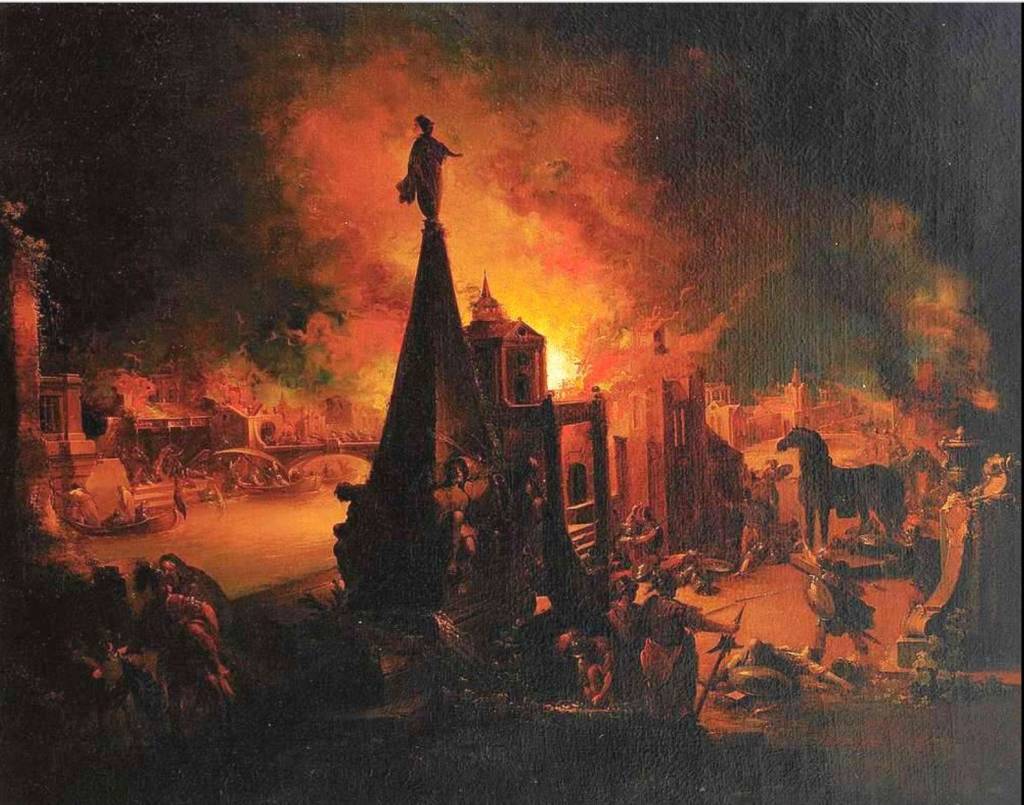

Jean MacKay Jackson: ‘War’

Some say that war is bright flares and drama,

A glory of fireworks illumining skies.

This is all lies.

War is a child calling out for his mama

And getting no answer.

War is a merchant of hatred and grief:

War is a thief,

War is a cancer.

Some say that war is hell. Perhaps that is so.

Yet hell has a lack

Of innocent bystanders, hell has no

Collateral damage, no accidental black

Body-bags for old women and babies.

Hell has no maybes;

Everything makes sense.

In hell there is no defense:

You belong there. You chose your path.

Hell has a cold, hard justice drained of wrath.

War is the horrified look in the eye

Of a young person dying without knowing why.

Tom Vaughan: ‘Aleppo’

Never again we say, each time

never, never again,

and every time we mean it so

when it happens again

we watch it on our screens, and say

never, never again

we meet and vote and all agree

never, never again.

Marcus Bales: ‘Genocide is Genocide’

Genocide is genocide. There’s no

Legitimacy on the table. None.

Your killing and your maiming only show

What horrors piled on horrors you have done.

The US taught the method to the Germans

The Trail of Tears leads to the Holocaust.

And now Israeli policy determines

They’ll do the same in Gaza. That boundary’s crossed.

Why not, instead, a reconciliation,

Where all the old and evil wounds can be

Accepted by each side without probation?

With zealotry forgiven, all are free.

Until that happens, hate corrupts you all,

With “Ams Yisrael Chai” the new decree —

Unless it turns out that the final call

That wins is “From the river to the sea.”

And that’s the choice: that each side does the worst

That it can do to keep the hatreds growing,

Shouting slogans of revenge, and cursed

To trade atrocities that keep the business going.

The other choice is reconciliation.

Yes, all the old and evil wounds will be

Accepted by each side without probation,

And zealotry forgiven, to be free.

If “Look at what they did to us!” is your

Refrain, then all you’ve done is to condemn

Your children to a world where they’ll endure

Their children’s gloat: “Look what we did to them!”

There’s always someone left to live resenting

The evils your revenges made you do —

And they will spend their hearts and souls inventing

A suitable revenge to take on you.

Be strong enough for reconciliation

Where all the old and evil wounds must be

Accepted by each side without probation.

With zealotry forgiven, all are free.

Michael R. Burch: ‘Epitaph for a Palestinian Child’

I lived as best I could, and then I died.

Be careful where you step: the grave is wide.

*****

Acknowledgements:

Leo Yankevich: ‘The Terrorist’, collected in ‘Tikkun Olam & other poems’, Counter Currents, 2012

Tom Vaughan: ‘The Land’, published on Hull University Middle East Study Centre website, 2022, and in Professor Raphael Cohen-Almagor’s December 2022 Politics Newsletter

Tom Vaughan: ‘Aleppo’, published in Snakeskin 233, October 2016

Michael R. Burch: ‘Epitaph for a Palestinian Child’, first published in Romantics Quarterly, and many places since. Michael R. Burch is the founder and editor-in-chief of The HyperTexts, and its extensive collections of poetry include ones on both the Holocaust and the Nakba.

Photo: “Gaza war Nov2012” by EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.