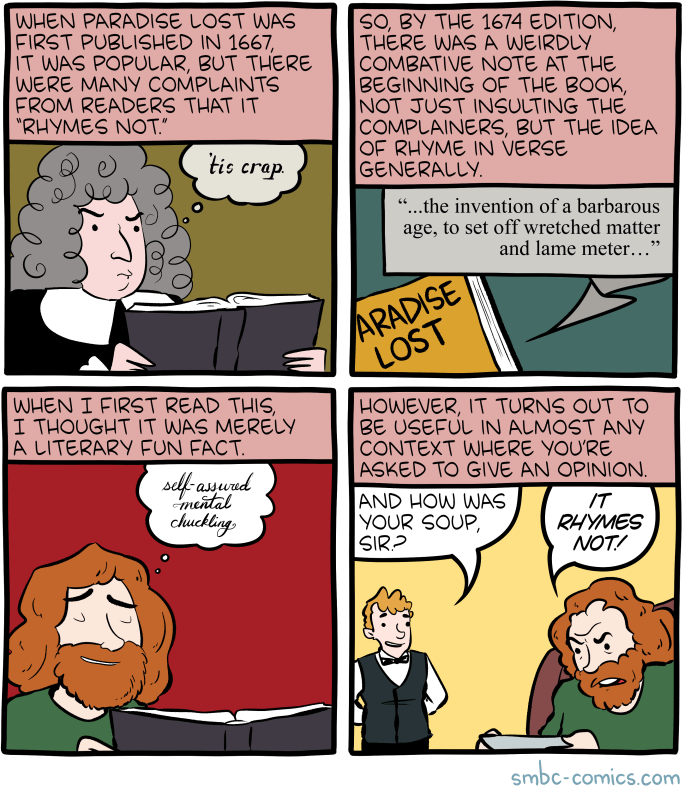

John Milton was perfectly capable of expressing himself in rhyme, as in his Petrarchan sonnet on his blindness, When I Consider How My Light Is Spent. Paradise Lost attracted a lot of criticism for its boring lack of rhyme (as well as a lot of unthinking religious approval for its wretched matter). At the front of the second edition of his Paradise Lost in 1674, John Milton defends his books-long use of blank verse:

“The measure is English heroic verse without rime, as that of Homer in Greek, and of Virgil in Latin—rime being no necessary adjunct or true ornament of poem or good verse, in longer works especially, but the invention of a barbarous age, to set off wretched matter and lame metre; graced indeed since by the use of some famous modern poets, carried away by custom, but much to their own vexation, hindrance, and constraint to express many things otherwise, and for the most part worse, than else they would have expressed them. Not without cause therefore some both Italian and Spanish poets of prime note have rejected rime both in longer and shorter works, as have also long since our best English tragedies, as a thing of itself, to all judicious ears, trivial and of no true musical delight; which consists only in apt numbers, fit quantity of syllables, and the sense variously drawn out from one verse into another, not in the jingling sound of like endings—a fault avoided by the learned ancients both in poetry and all good oratory. This neglect then of rime so little is to be taken for a defect, though it may seem so perhaps to vulgar readers, that it rather is to be esteemed an example set, the first in English, of ancient liberty recovered to heroic poem from the troublesome and modern bondage of riming.”

Tell that to Geoffrey Chaucer; his Canterbury Tales is longer, rhymed, more varied and more engaging. As Samuel Johnson wrote, “Milton formed his scheme of versification by the poets of Greece and Rome, whom he proposed to himself for his models so far as the difference of his language from theirs would permit the imitation.” And that’s the problem: Greek and Latin poems are simply not appropriate models for a Germanic language’s poetry.

One of the benefits of rhyme is that it prevents a writer from rambling on fluffily and indefinitely, the way anyone capable of writing blank verse can do. Indeed, when you look at a modern poet’s recent collection you are likely to see short, tight half-page pieces that rhyme, and longer, looser multi-page pieces that don’t. I invariably prefer the former. I find them more enjoyable to read, more succinctly expressed, easier to appreciate, more fun to remember and quote. The others are just lazy, uninspired fillers, or politico-religious pamphlets where zeal has replaced poetry… cf. Paradise Lost.

Illustration: ‘Rhymes‘ by Zach Weinersmith, who publishes a Saturday Morning Breakfast Comics (or SMBC) cartoon daily. He is the author of several brilliant and provocative books, including the previously reviewed ‘Shakespeare’s Sonnets: Abridged Beyond the Point of Usefulness‘.