We hadn’t pictured paradise

with vultures circling overhead.

Edenic lushness has a price

we hadn’t pictured. Paradise

seems changeless, but its clock’s precise.

“It’s feeding time,” the watchers said.

We hadn’t pictured paradise

with vultures, circling overhead.

*****

Susan McLean writes: “This triolet was inspired partly by the Latin phrase “Et in Arcadia ego” (which means “I too [am or was] in Arcadia”), partly by the famous Nicolas Poussin painting in which that phrase appears on a tombstone surrounded by gawking Arcadian shepherds, and partly by a family trip to Florida at Christmas, to celebrate my parents’ sixtieth wedding anniversary. Arcadia, a region in Greece, was made famous by Vergil in his Eclogues as an idyllic rural land mainly populated by shepherds. “Arcadia” thus came to be associated with a relaxed bucolic paradise. Yet the Latin phrase reminds us that no earthly location is immune to death.

“In contemporary America, one of the locations associated with tropical warmth and pleasant leisure is Florida, where many Americans from more northerly locales go to vacation or retire. While my family was staying at a rented home near Sarasota Bay, on the highway we often passed signs for Arcadia, Florida, which was not far away. The weather and the natural beauty of Sarasota came up to our expectations, but we did not foresee that every time we went outside we would see vultures circling overhead. Given our parents’ ages, the vultures were a poignant reminder of mortality.

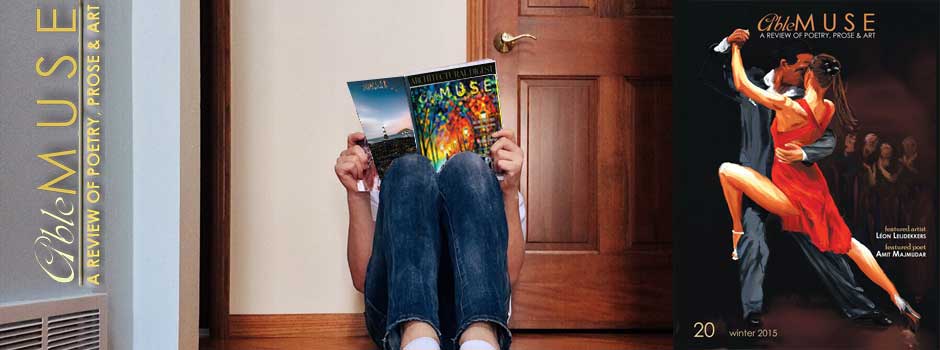

“A triolet is one of the shorter French repeating forms. One of the challenges it presents is how to vary the repeated lines so that they do not become boring, usually done by adding slight changes to the punctuation of those lines. This poem originally appeared in Able Muse and later in my second poetry book, The Whetstone Misses the Knife.”

Susan McLean has two books of poetry, The Best Disguise and The Whetstone Misses the Knife, and one book of translations of Martial, Selected Epigrams. Her poems have appeared in Light, Lighten Up Online, Measure, Able Muse, and elsewhere. She lives in Iowa City, Iowa.

https://www.pw.org/content/susan_mclean

Photo: “Road Trip Santa Clara to Camajuani via Central Road of Cuba (banda Placetas) passing through La Movida, Pelo Malo, Manajanabo, Miller town and Falcon city. Villa Clara province, Cuba, November 2023” by lezumbalaberenjena is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.