Wheer ‘asta beän saw long and meä liggin’ ‘ere aloän?

Noorse? thoort nowt o’ a noorse: whoy, Doctor’s abeän an’ agoän;

Says that I moänt ‘a naw moor aäle; but I beänt a fool;

Git ma my aäle, fur I beänt a-gawin’ to breäk my rule.

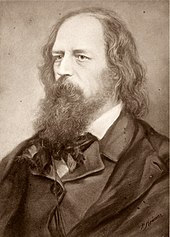

This is the opening stanza of Alfred, Lord Tennyson‘s poem ‘The Northern Farmer: Old Style’. The farmer is dying, but obstinately overrules the doctor’s order that he not drink any more ale, just as he obstinately clings to traditional attitudes towards land and class, farming and money.

Where have you been so long and me lying here alone?

Nurse? You’re no good as a nurse; why, the doctor’s come and gone:

Says that I mayn’t have any more ale; but I’m not a fool;

Get me my ale, because I’m not going to break my rule.

It’s one of a series of poems he wrote that recapture the dialect of his Lincolnshire youth, and that reflect the old traditions and the modern changes of that part of the country. It is paired specifically with ‘The Northern Farmer: New Style’–Here the “new style” farmer, out in a cart with his son Sammy, hears the horse’s hooves clip-clopping “Property, property” and chides his son for not thinking enough about money:

Me an’ thy muther, Sammy, ‘as been a’talkin’ o’ thee;

Thou’s beän talkin’ to muther, an’ she beän a tellin’ it me.

Thou’ll not marry for munny–thou’s sweet upo’ parson’s lass–

Noä–thou ‘ll marry for luvv–an’ we boäth of us thinks tha an ass.

Seeä’d her todaäy goä by–Saäint’s-daäy–they was ringing the bells.

She’s a beauty, thou thinks–an’ soä is scoors o’ gells,

Them as ‘as munny an’ all–wot’s a beauty?–the flower as blaws.

But proputty, proputty sticks, an’ proputty, proputty graws.

or, in more modern words:

Me and your mother, Sammy, have been talking of you;

You’ve been talking to mother, and she’s been telling me.

You don’t want to marry for money–you’re sweet on the parson’s daughter–

No, you want to marry for love–and we both think you’re an ass.

Saw her today going by–Saint’s day–they were ringing the bells.

She’s a beauty, you think–and so are scores of girls,

Those with money and everything–what’s a beauty?–a flower that fades.

But property, property sticks, and property, property grows.

Tennyson was meticulous in trying to recapture the life and language of his youth. He wrote:

When I first wrote ‘The Northern Farmer’ I sent it to a solicitor of ours in Lincolnshire. I was afraid I had forgotten the tongue and he altered all my mid-Lincolnshire into North Lincolnshire and I had to put it all back.

And apart from the accuracy of the dialect, Tennyson was as skilled as ever with his carefully conversational metre, and natural rhymes working comfortably with the natural breaks of the lines.

The best ear of any English poet. These are seriously underrated poems that not only capture the idioms and speech patterns of Mid-Lincolnshire, but offer a profound social comment on the changing values of late Victorian England where attachment to the land has been replaced by an obsession with money and ‘property’.

Patrick Campbell

LikeLiked by 1 person

They’re hard work, especially for those whose English is not their first language. But highly enjoyable once you get inside the words and hear the old man’s speech.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Poetry rewards the patient reader, growing ever more intimate as fresh layers peek out. Many poems shine best when spoken — again, taking time to find the music in the words.

Tennyson is one poet whose works blossom this way. Expect to use your voice like a polishing cloth, swirling line by line, or buffing up one phrase.

Some words, to my ear and mind, read best without translation. With respect, here are two phrases I read differently, with poetry in mind:

Noorse? thoort nowt o’ a noorse…

Nurse? Thou art nowhat o’ a nurse… Is “thou art” too archaic to be understood in poetry? The word “nowhat” mimics “nowhere.” We would substitute “anyone” for “anywho,” perhaps, but is there any ambiguity? The melody of the speech leaves no confusion.

…but I beant a fool;

…but I be not a fool; Is a modern “am not” to be preferred over “be not,” which works well enough when Shakespeare bedevils young students? They get it on first reading, without translation, and anyway “is “be not” be not a grammatic error, particularly in poetry.

But perhaps some need the clarity while poetry stretches their thoughts. I celebrate all readers.

LikeLiked by 1 person