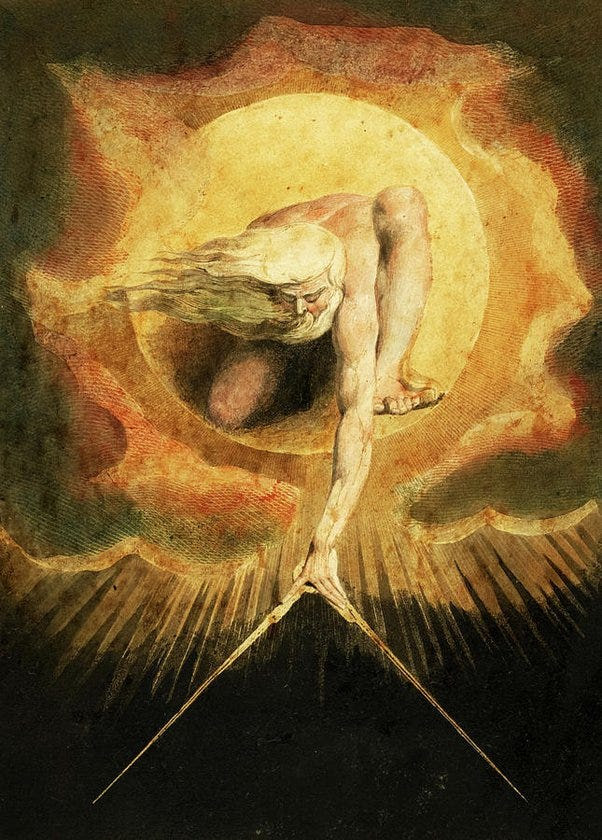

You’re smiling, nodding, entering some room

Where what weight you once swung you swung for years,

Acknowledging this or that one, most of whom

Are people you politely call your peers.

And like the step you miss that wasn’t there

Kaboom: the rush returns. Awareness bursts

Enormously inside and out, the where

And when, the who and why, the lasts, the firsts.

Then no one listens as you start to speak,

And there’s another, higher, step you miss.

You squint, and almost hear the leather creak,

But readiness is all there is of this.

Your saddlebags and holsters do not rate.

There’s nothing to fight out of if you can.

The ambush turns, indifferently, to wait

For something more than you. Move on, old man.

*****

Editor: I like this poem as it is. However there appears to be more backstory, and Marcus Bales assembles the following: an excerpt from ‘Lonesome Dove’, and Daniel Keys Moran’s comments, and Marcus Bales’ own comments:

After a few minutes the empty feeling passed, but Call didn’t get to his feet. The sense that he needed to hurry, which had been with him most of his life, had disappeared for a space.

“We might as well go on to Montana,” he said. “The fun’s over around here.”

Augustus snorted, amused by the way his friend’s mind worked.

“Call, there never was no fun around here,” he said. “And besides, you never had no fun in your life. You wasn’t made for fun. That’s my department.”

“I used the wrong word, I guess,” Call said.

“Yes, but why did you?” Augustus said. “That’s the interesting part.”

Call didn’t feel like getting drawn into an argument, so he kept quiet.

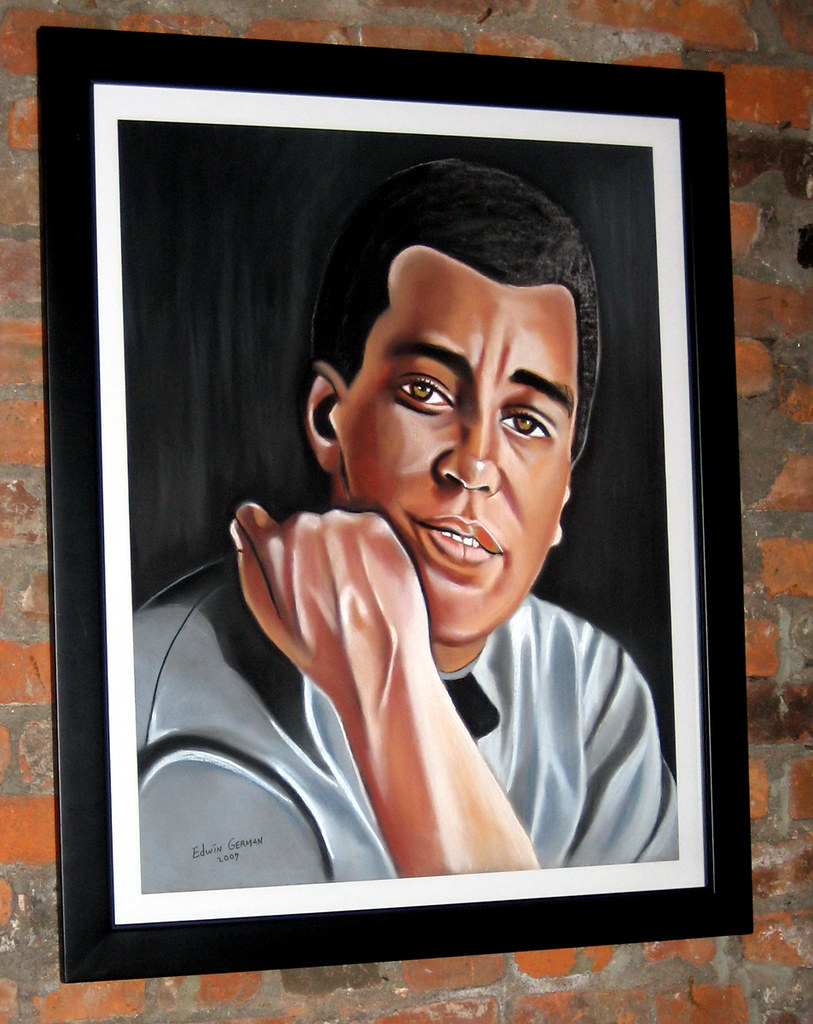

“First you run out of Indians, now you’ve run out of bandits, that’s the pint,” Augustus said. “You’ve got to have somebody to outwit, don’t you?”

“I don’t know why I’d need anybody when I’ve got you,” Call said.

Even though he still came to the river every night, it was obvious to Call that Lonesome Dove had long since ceased to need guarding. The talk about Bolivar calling up bandits was just another of Augustus’s overworked jokes. He came to the river because he liked to be alone for an hour, and not always be crowded. It seemed to him he was pressed from dawn till dark, but for no good reason. As a Ranger captain he was naturally pressed to make decisions—and decisions that might mean life or death to the men under him. That had been a natural pressure—one that went with the job. Men looked to him, and kept looking, wanting to know he was still there, able to bring them through whatever scrape they might be in. Augustus was just as capable, beneath all his rant, and would have got them through the same scrapes if it had been necessary, but Augustus wouldn’t bother rising to an occasion until it became absolutely necessary. He left the worrying to Call—so the men looked to Call for orders, and got drunk with Augustus. It never ceased to gripe him that Augustus could not be made to act like a Ranger except in emergencies. His refusal was so consistent that at times both Call and the men would almost hope for an emergency so that Gus would let up talking and arguing and treat the situation with a little respect.

But somehow, despite the dangers, Call had never felt pressed in quite the way he had lately, bound in by the small but constant needs of others. The physical work didn’t matter: Call was not one to sit on a porch all day, playing cards or gossiping. He intended to work; he had just grown tired of always providing the example. He was still the captain, but no one had seemed to notice that there was no troop and no war. He had been in charge so long that everyone assumed all thoughts, questions, needs and wants had to be referred to him, however simple these might be. The men couldn’t stop expecting him to captain, and he couldn’t stop thinking he had to. It was ingrained in him, he had done it so long, but he was aware that it wasn’t appropriate anymore. They weren’t even peace officers: they just ran a livery stable, trading horses and cattle when they could find a buyer. The work they did was mostly work he could do in his sleep, and yet, though his day-to-day responsibilities had constantly shrunk over the last ten years, life did not seem easier. It just seemed smaller and a good deal more dull.

Call was not a man to daydream—that was Gus’s department—but then it wasn’t really daydreaming he did, alone on the little bluff at night. It was just thinking back to the years when a man who presumed to stake out a Comanche trail would do well to keep his rifle cocked. Yet the fact that he had taken to thinking back annoyed him, too: he didn’t want to start working over his memories, like an old man. Sometimes he would force himself to get up and walk two or three more miles up the river and back, just to get the memories out of his head. Not until he felt alert again—felt that he could still captain if the need arose—would he return to Lonesome Dove.

“Ambush” developed out of following Daniel Keys Moran on F*c*book. For some time now he has been posting about coming changes in his life, one of which is retirement from the work-force. My poem actually has no connection to his situation at all, apart from my also having retired. He was a much bigger deal, in charge of a lot more than I ever was, in any of my endeavors, but within my limits I was usually in charge of whatever small enterprises I participated in. I imagine the experience of going from being in charge to being supernumary is about the same, internally, for everyone.

Moran posted the excerpt from McMurtry’s “Lonesome Dove” just recently, as, I inferred, a comment and possibly a reflection on his situation. It certainly resonated with me. Of course Call, the Captain in “Lonesome Dove”, and Moran, and the narrator of “Ambush” all have different situations and different reactions. But there is, I think a family resemblance.

*****

Not much is known about Marcus Bales except that he lives and works in Cleveland, Ohio, and that his work has not been published in Poetry or The New Yorker. However his ‘51 Poems‘ is available from Amazon. He has been published in several of the Potcake Chapbooks (‘Form in Formless Times’).

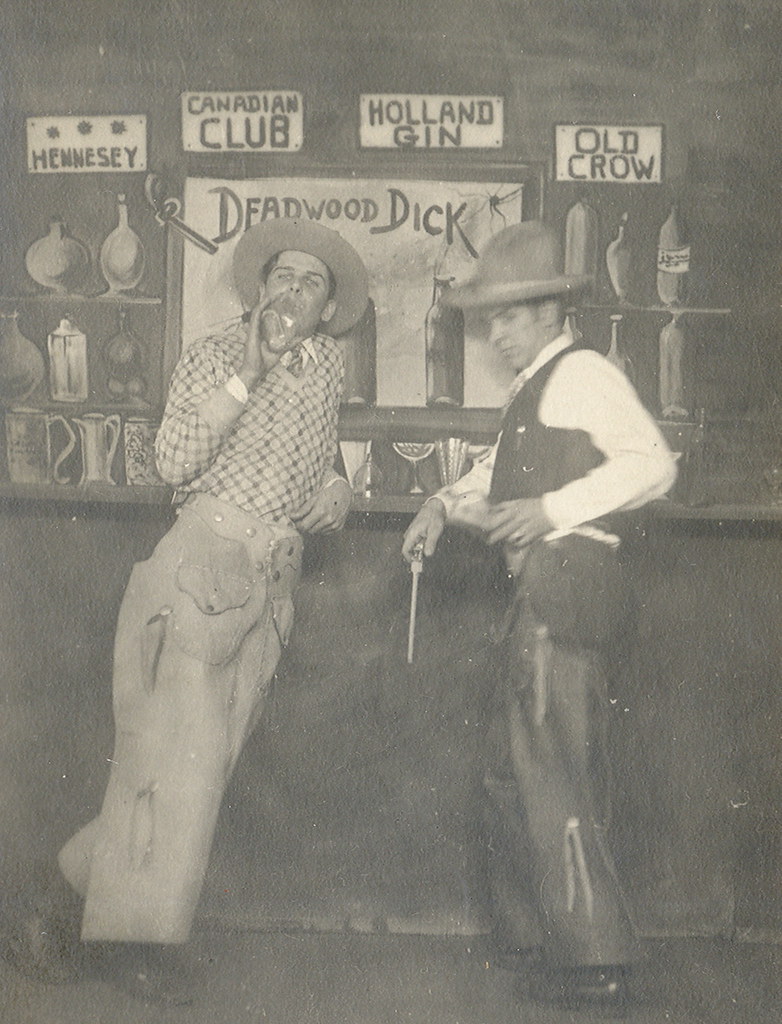

Photo: “Real Photo Hard Drinking Handsome Cowboys at the Deadwood Dick Saloon Studio Photograph RPPC AZO Stamp Box Hennesy Canadian Club Holland Gin Old Crow 2” by UpNorth Memories – Don Harrison is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.