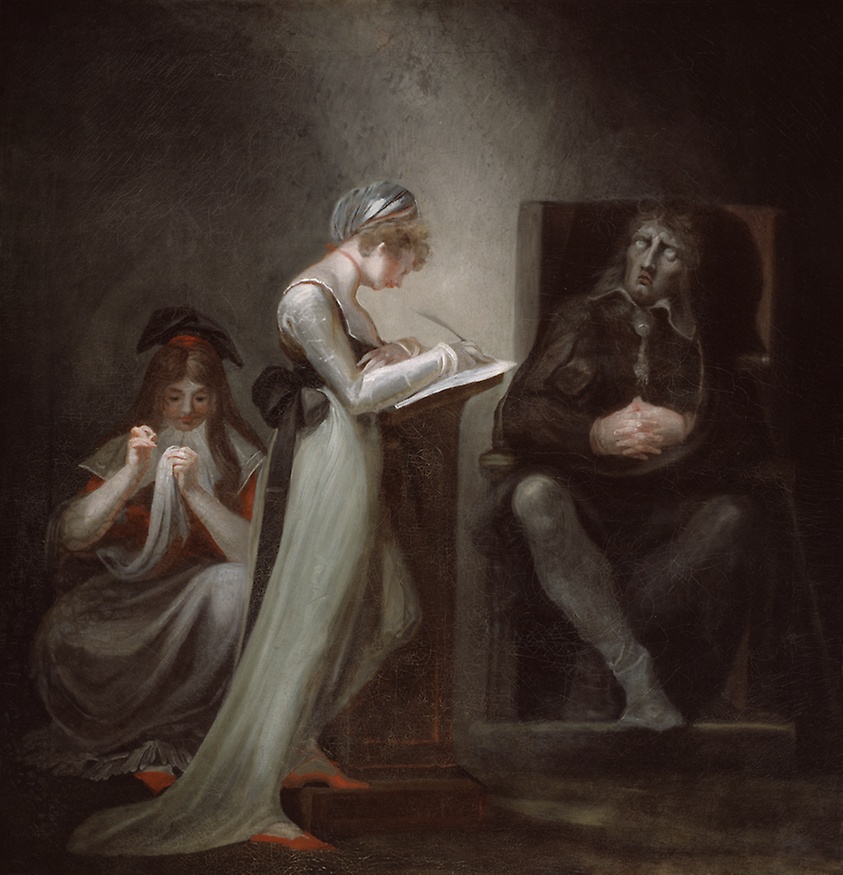

a homage to Donne’s ‘Nocturnal on St Lucies day’

The shortest day is soon. Time for a pact.

I don’t mean with Saint Lucy (Lucy’s day

falls earlier in the month). But hey

let’s meet and talk and counteract

such darkness of the heart

as coincides with winter’s formal start.

We can read Donne’s ‘Nocturnal’, view its art,

its provenance and what on earth it means.

Location doesn’t matter. We have screens.

Nobody writes a poem now like that —

not something so precise and well controlled.

Of course, we hear what we are told:

the world is round, a rhyme is flat,

‘poetics’ have moved on

and these days no-one wants to write like Donne

who was amazing, right? But dead and gone.

Or not that dead. I’d say he’s still alive

in stanza three and certainly in five.

They call Donne ‘metaphysical’, you know,

a word still popular in jacket blurbs

for living, writing bards where verbs

(or verbiage) propel the flow

but hard now to be sure

whether they mean what Johnson meant. The more

‘meta’ you get with blurbs, the more obscure.

When ‘metaphysical’ foretells a treat

it might be true; it might be mere conceit.

But in ‘Nocturnal’, metaphor leans out

and mystifies. It’s not the usual thing

like glass or compasses or string.

It’s nothing. No thing. Less than nowt.

He says what he is not

in several different ways. In fact, the knot

of nothingness becomes his central plot.

The poet in him can’t forget that ‘none’,

his rhyme for ‘run’, echoes both ‘sun’ and ‘Donne’.

So he’s the sum of everything he feels:

annihilated by the loss of one

without whom he is not a man,

just numb. And yet he still appeals

to logic to make clear

how dark existence is. Yes, she was dear.

Each syllable recounts her loss, his fear,

and this is now and then and now, since this

both the year’s and the day’s deep midnight is.

*****

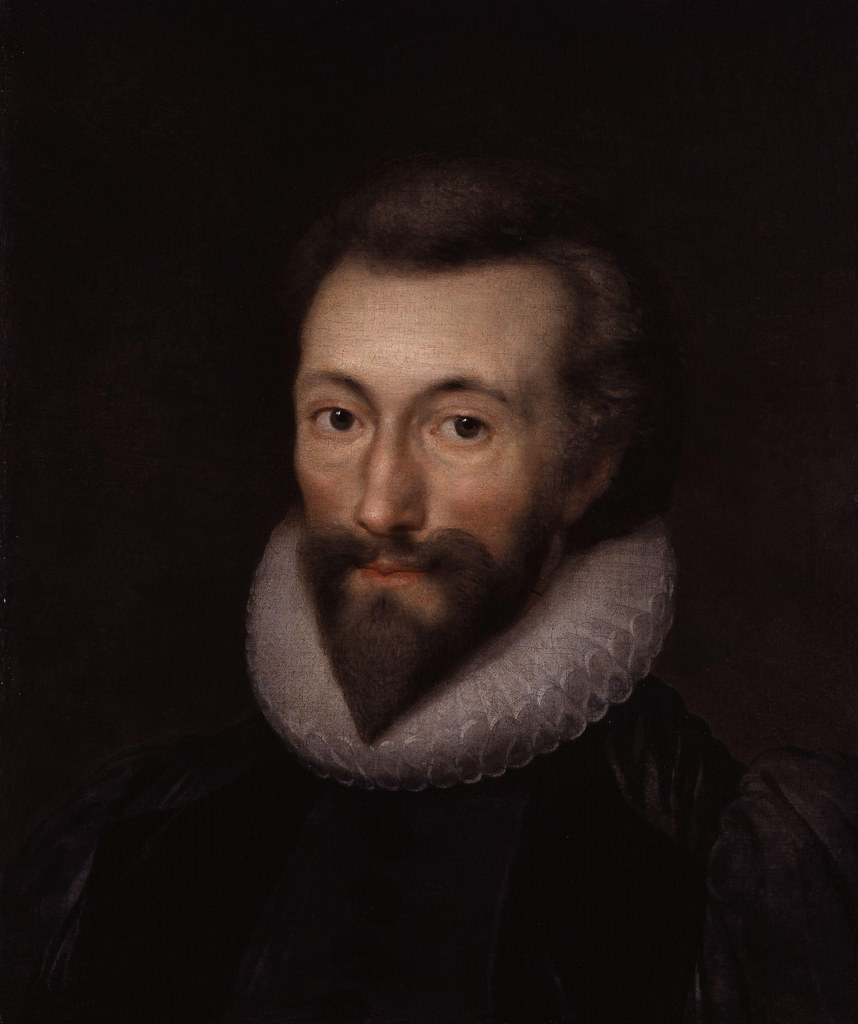

Helena Nelson writes: “In 1617 when, after the death of his wife, John Donne wrote ‘A nocturnall upon S. Lucies day, Being the shortest day’, St Lucy’s Day coincided with the winter solstice in the author’s hemisphere. Then they changed the calendar, and these days, Saint Lucy’s Day is 13 December. But the winter solstice falls over a week later (this year 21 December).

“Every year on the solstice, I think about John Donne’s solstice poem, every year it gets more apposite, since it is essentially about death. Last year, I did a formal online discussion about it, and I wrote an invitation using the form that is Donne’s, though obviously for a less serious purpose. It allowed me to think it through. I’m thinking about the poem again today, so here’s the invitation.”

Helena Nelson runs HappenStance Press (now winding down) and also writes poems. Her most recent collection is Pearls (The Complete Mr and Mrs Philpott Poems). She reviews widely and is Consulting Editor for The Friday Poem.

Photo: “John Donne, Poet” by lisby1 is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0.