An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying king,–

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn, mud from a muddy spring,–

Rulers who neither see, nor feel, nor know,

But leech-like to their fainting country cling,

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow,–

A people starved and stabbed in the untilled field,–

An army which liberticide and prey

Makes as a two-edged sword to all who wield,–

Golden and sanguine laws which tempt and slay;

Religion Christless, Godless, a book sealed,–

A Senate—Time’s worst statute unrepealed,–

Are graves from which a glorious Phantom may

Burst to illumine our tempestuous day.

Shelley wrote this sonnet in 1819 in response to the Peterloo Massacre: a peaceful crowd of 60,000 had gathered in Manchester to call electoral reform, but were charged into by a local Yeomanry regiment, and then by a cavalry regiment of the King’s Hussars with sabres drawn. Official numbers show 18 people killed, including several women, and 400 to 700 injured: bayoneted, sabred, knocked down, trampled.

Shelley blames the mad King George III and his sons (including of course the Regent, the future George IV), and the ruling class in a time of unemployment and economic recession, and further blames the illiberal army, and harsh laws, and morality-free religion, and a Parliament that was refusing all civil rights to Catholics. They might all be graves of corruption, but Shelley hopes that from their decay will come a glorious new spirit to brighten the world.

Not all of the poem resonates with any particular political situation in the world today; but “an old, mad, blind, despised and dying king”… well, that’s certainly the impression given by the White House in early 2021.

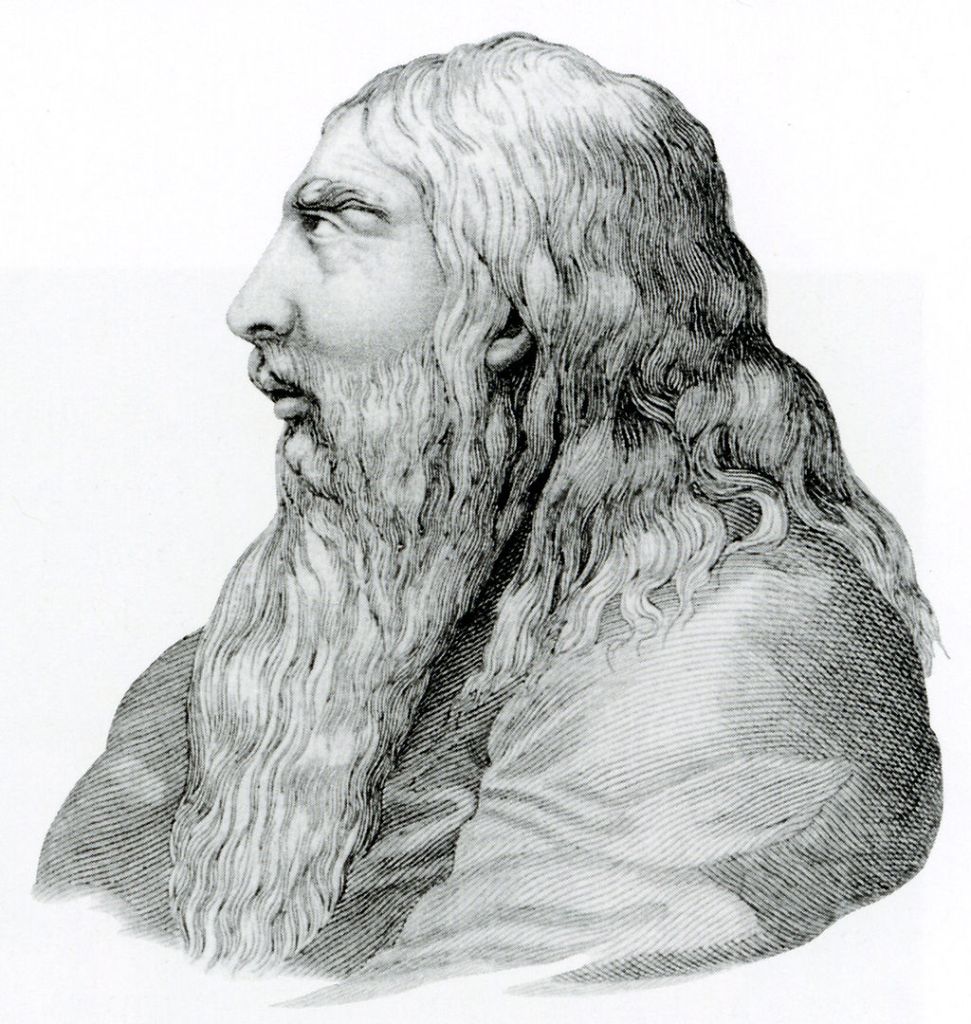

Technically: the sonnet is in iambic pentameter as you would expect, but the rhyme scheme is unconventional: ababab cdcdccdd. The illustration is an engraving of George III in later life, by Henry Meyer.