O my luve’s like a red, red rose

That’s newly sprung in June:

O my luve’s like the melodie

That’s sweetly play’d in tune.

So fair art thou, my bonnie lass,

So deep in luve am I;

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

Till a’ the seas gang dry.

Till a’ the seas gang dry, my dear,

And the rocks melt wi’ the sun:

And I will love thee still, my dear,

While the sands o’ life shall run.

And fare thee weel, my only luve!

And fare thee weel awhile!

And I will come again, my luve,

Tho’ it were ten thousand mile!

*****

January 25th being the birthday of Robert Burns (and the opportunity for a Burns Night celebration), it seems the right day to post an interesting fact that I was unfamiliar with until reading a 1964 Canadian high school poetry text book: ‘A Red, Red Rose’ was fashioned from three distinct songs that Burns had heard in the Highlands of Scotland. Part of each song was reworked by him into a single poem:

(Song 1)

Her cheeks are like the roses

That blossom fresh in June;

O, she’s like a new-strung instrument

That’s newly put in tune.

(Song 2)

The seas they shall run dry,

And rocks melt into sands

Then I’ll love you still, my dear,

When all these things are done.

(Song 3)

Altho’ I go a thousand miles

I vow thy face to see,

Altho’ I go ten thousand miles,

I’ll come again to thee, dear love,

I’ll come again to thee.

Wikipedia (as often) is a good place to look for more information, and here is an extensive quotation from its article on the poem:

Sources

Burns is best understood as a compiler or a redactor of “A Red, Red Rose” rather than its author. F.B. Snyder wrote that Burns could take “childish, inept” sources and turn them into magic, “The electric magnet is not more unerring in selecting iron from a pile of trash than was Burns in culling the inevitable phrase or haunting cadence from the thousands of mediocre possibilities.”

One source that is often cited for the song is a Lieutenant Hinches’ farewell to his sweetheart, which Ernest Rhys asserts is the source for the central metaphor and some of its best lines. Hinches’ poem, “O fare thee well, my dearest dear”, bears a striking similarity to Burns’s verse, notably the lines which refer to “ten thousand miles” and “Till a’ the seas gang dry, my dear”.

A ballad originating from the same period entitled “The Turtle Dove” also contains similar lines, such as “Though I go ten thousand mile, my dear” and “Oh, the stars will never fall down from the sky/Nor the rocks never melt with the sun”. Of particular note is a collection of verse dating from around 1770, The Horn Fair Garland, which Burns inscribed, “Robine Burns aught this buik and no other”. A poem in this collection, “The loyal Lover’s faithful promise to his Sweet-heart on his going on a long journey” also contains similar verses such as “Althou’ I go a thousand miles” and “The day shall turn to night, dear love/And the rocks melt in the sun”.

An even earlier source is the broadside ballad “The Wanton Wife of Castle-Gate: Or, The Boat-mans Delight”, which dates to the 1690s. Midway through the ballad, Burns’ first stanza can be found almost verbatim: “Her Cheeks are like the Roses, that blossoms fresh in June; O shes like some new-strung Instrument thats newly put in tune.” The provenance for such a song is likely medieval.

Thank you, Wikipedia! Love you!

And everyone: Have a good Rabbie Burns Day!

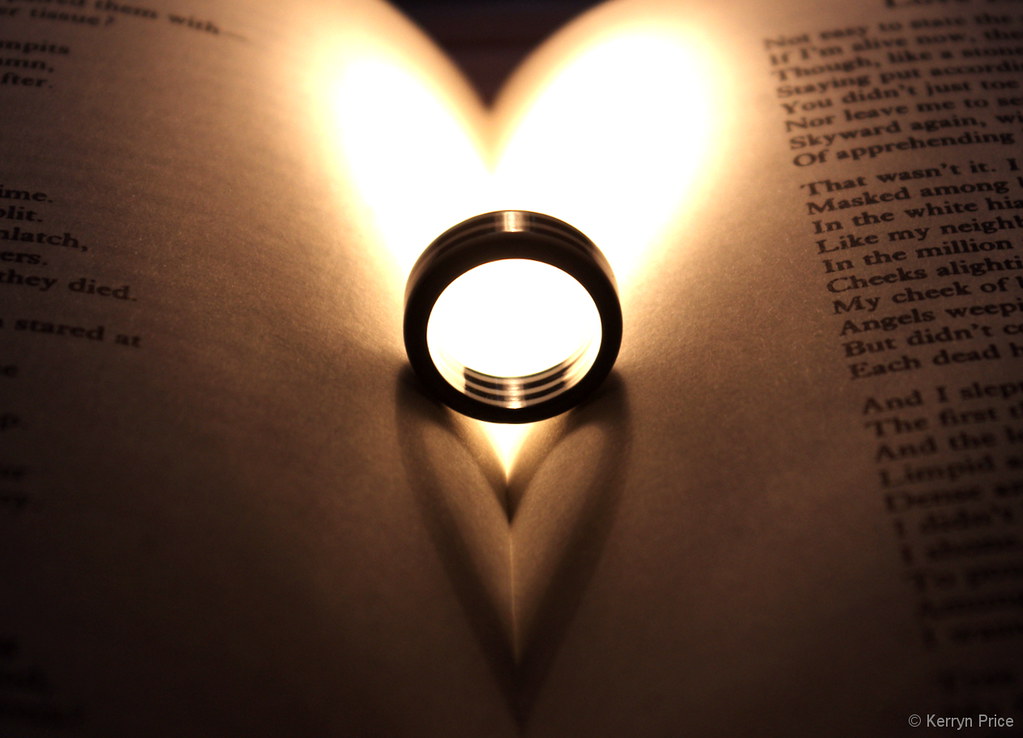

“O my Luve’s like a red, red rose that’s newly sprung in June” by Cait Clerin is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. The work is ‘A Summer Bouquet’ by George Elgar Hicks, 1878.