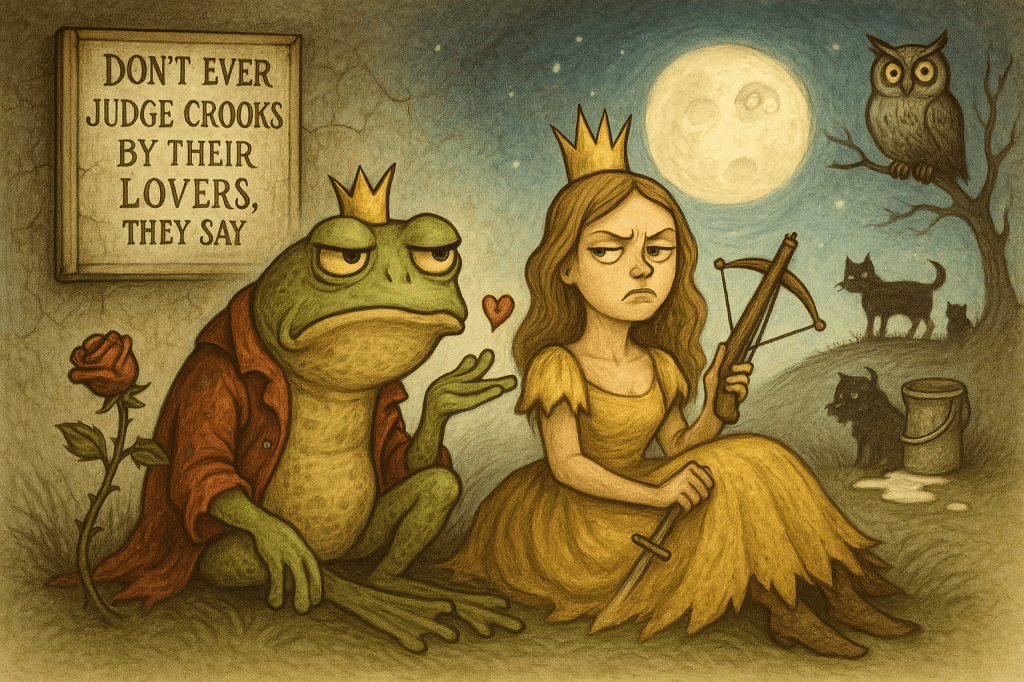

Don’t ever judge crooks by their lovers, they say

On book covers nailed to the wall.

The frog sends his kiss at the bend of the day

To Belle who is beast of the ball.

As tough as a cucumber, cool as old boots,

An untroubled damsel of flair

Is shooting for stars. When the pussy-owl hoots

She snares a short prince with blonde hair.

They sail inky skies on a silver-lined dream

To greener scenes up in the hills.

But honey and moons aren’t as sweet as they seem

When cats and dogs reign and milk spills.

His rose bears a thorn and his shoulder, a chip.

Hyenas have stolen his laughter.

All charm hits the skids as she grapples to slip

The grip of his gripe ever after.

*****

Susan Jarvis Bryant writes: “I really don’t have anything to say about the poem, other than I had huge fun writing it. It’s the same with all of my poems – I never suffer for my art, which makes me reluctant to call myself a poet. I’d like to say I write my poems in a tearstained, whisky-soaked haze while my Muse tangos with the ghost of Dylan Thomas through Welsh valleys, but this is not so. I just snigger away as the ink flows like a bad comedienne laughing at her own jokes.”

‘Once Upon a Tortured Trope’ was originally published in Snakeskin.

Susan Jarvis Bryant is originally from the U.K. and now lives on the coastal plains of Texas. Susan has poetry published on The Society of Classical Poets, Lighten Up Online, Snakeskin, Light, Sparks of Calliope, and Expansive Poetry Online, The Road Not Taken, and New English Review. She also has poetry published in The Lyric, Trinacria, and Beth Houston’s Extreme Formal Poems and Extreme Sonnets II anthologies. Susan is the winner of the 2020 International SCP Poetry Competition and was nominated for the 2022 and 2024 Pushcart Prize. She has published two books – Elephants Unleashed and Fern Feathered Edges.

Art: AI + RHL