Why are we here in the agora, say?

We’ve got the Barbarians coming today.

Why are the senators resting their jaws?

Why don’t they legislate? What about laws?

We’ve got the Barbarians coming today.

Nobody knows how it’s going to play;

If any legislate, it will be they.

Why is our Emperor out of his bed,

Sitting in state at the gate there instead,

Wearing a gorgeous great crown on his head?

We’ve got the Barbarians coming today.

They must be met in an elegant way:

Greeting their chieftain, the Emperor’s goal

Is to award him an exquisite scroll,

Giving him titles to make his eyes roll.

Why do our consuls and praetors appear

Dressed to the nines in their purplest gear?

Why are there amethysts all up their arms,

Emeralds everywhere, greener than palms?

What are those fabulous sceptres they hold,

Fancily fashioned in silver and gold?

We’ve got the Barbarians coming today.

This sort of thing’s their idea of cachet.

Why are our orators keeping us waiting,

Not, as per usual, loudly orating?

We’ve got the Barbarians coming today.

Oratory bores them. They like a display.

Why does it suddenly seem such a mess?

Why the confusion, the seriousness?

Why is there emptiness now in the square?

Why the pervasively secretive air?

Not one of them came, and the day is now done.

People are saying the war has been won;

Hence there are no more Barbarians. None.

No more Barbarians – what shall we do?

I’ve not come up with an answer yet.

You?

*****

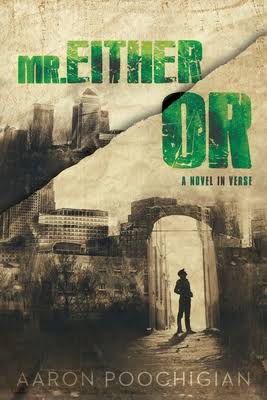

Julia Griffin writes: “I’ve always loved Cavafy’s ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’ and had the thought that it would go well into rhyme. This somehow necessitated changing the ending a little…” Her translation appears in the current Lighten Up Online.

See also the Wikipedia article, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waiting_for_the_Barbarians_(poem)

Julia Griffin lives in south-east Georgia/ south-east England. She has published in Light, LUPO, Mezzo Cammin, and some other places, though Poetry and The New Yorker indicate that they would rather publish Marcus Bales than her. Much more of her poetry can be found through this link in Light.

Photo: “Barbarian looking but a real cool dude (8197985443)” by Frank Kovalchek from Anchorage, Alaska, USA is licensed under CC BY 2.0.