Post this, post that, post-modernists –

Denying narrative’s cabal.

The story that they tell insists

It’s not a story after all.

New Criticism made them see

That reading closely what was said

Meant cutting off biography,

And authors might as well be dead.

Like raisin oatmeal cookies, picked

In hopes of chocolate chip, they bust

Your faith in how things seem. You’re tricked

To only trust in doubting trust.

Without the person or the text,

No human mind, no human heart,

I guess we know what’s coming next:

Let the AIs do the art.

*****

Marcus Bales writes: “This is one of what I call my habitual poems. I have a perfectly good stand-alone idea, and start to work on it, but the parody turntable in my head takes over and the needle slides down into the groove and instead of stealing only the world-weary and faintly snarky Larkin tone it turns out I steal the whole poem.

I have a file of these to be revised away from parody and into something that is less parodic, or at least less immediately noticeable as theft.

The problem is I’m lazy about this stuff. There is a straightforward tradition of doing these kinds of parodicish things in song, called ‘filks’, and I’ve done some of them. It’s carried over into the same sort of thing in poems. The groove is there, the tonality is familiar, the original is familiar, and like the soap coming out of your hand in the shower, clunk, it hits the floor.

So, since Robin asked me to write this, I’ve got a revised version for you. It loses some of the immediacy of Larkin’s opening, of course, but I’ll bet if you hadn’t got that in your head associated with this one first, this second version would only have marked a faint echo — and you might not of noticed how Larkinesque it is at all.”

Editor’s note: Bales revised the first and fifth lines; the originals read:

They fuck you up, post-modernists,

(…)

But others fucked them up to see

Hence his Larkin references.

Not much is known about Marcus Bales except that he lives and works in Cleveland, Ohio, and that his work has not been published in Poetry or The New Yorker. However his ‘51 Poems‘ is available from Amazon. He has been published in several of the Potcake Chapbooks (‘Form in Formless Times’).

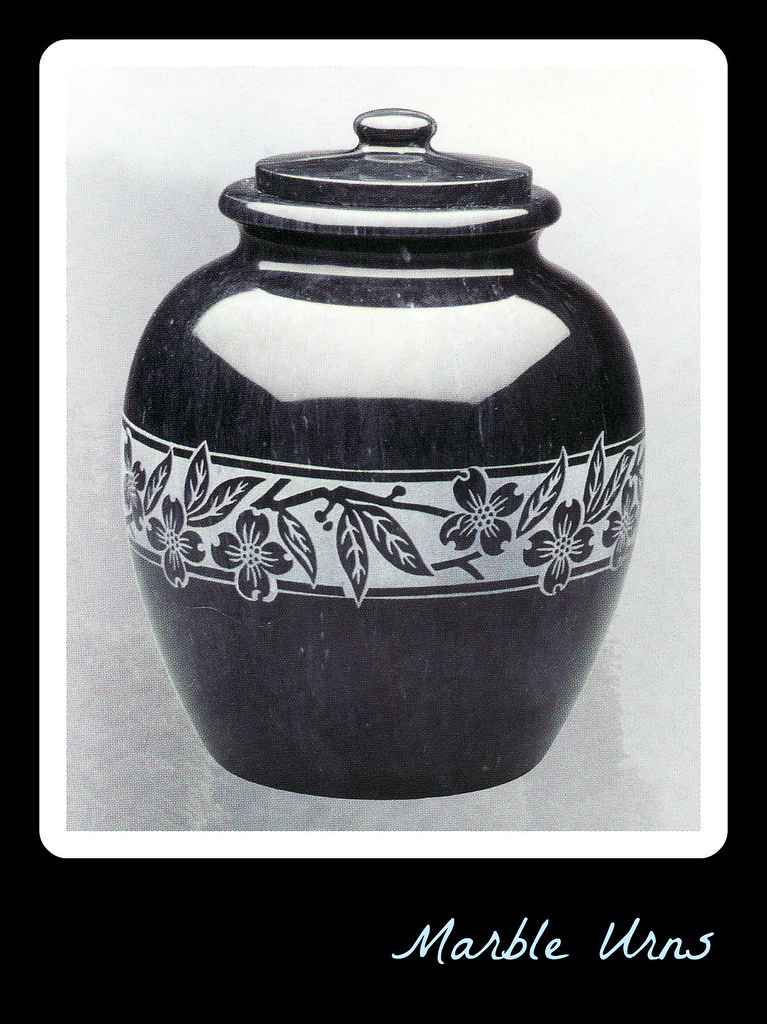

Photo: “Post-Modern Urinal” by ~MVI~ (warped) is licensed under CC BY 2.0.