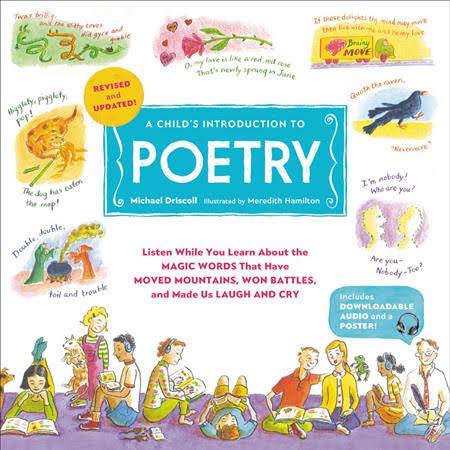

This book, “A Child’s Introduction to Poetry” by Michael Driscoll, illustrated by Meredith Hamilton, is the single best introduction to poetry that I have ever seen. It is part of a series of books aimed at 8 to 10-year-olds, and is divided into two parts: ‘The Rhymes and Their Reasons’, with two to four large pages on topics as diverse as Nonsense Rhymes, The Villanelle, Free Verse and Poems Peculiar; and ‘Poetry’s Greats’ with a couple of pages each on 21 poets such as Homer, Wordsworth, Dickinson, Belloc, Auden, Paz and Angelou. The book is richly illustrated on every page, and is packed with bits of biography, commentary, prosody, explanation and definition. Purely as a book, it is superb.

But wait! There’s more! The original edition came with a CD of all the poems, and the Revised and Updated edition comes with downloadable audio and a poster. These audio aspects are not as brilliant as the book, for two reasons: first, the poems are read “professionally” which unfortunately means without the joy, excitement, teasing, energy or naturalness that I listened for. They are clear, flat and boring, with unnecessarily exaggerated pauses between lines. I listened to the first three poems, and quit. Secondly, the CD version (which is what I have) may have been obsoleted, but the major item of comment in the Amazon reviews is that there are no explanations for downloading the audio, and that it was difficult for reviewers to figure out how to do it.

Ignore the audio, then. If you already have an interest in poetry you will probably do a better job than the unfortunate “professionals” in reading aloud from the book, and your child will have a richer experience anyway from your personal involvement and introduction. The book will soon enough be one for the child to dip into and skip back and forth in, moving from biographies to poems to illustrations to factoids as the mood takes them.

In terms of the variety of poetry–forms, moods, eras, nationalities–I have never seen anything so rich and satisfying for a good young reader as this Introduction. I wish all English-speaking children everywhere could have a copy.