I remember you some mornings in the midst of getting dressed

Surprised that I recall exactly when I wore you last

The paisley patterns spilling over sleeves

The Nehru collars nobody believes

… were popular

The turtlenecks no turtle ever wore

Those V-neck disco shirts that dance no more

… Spectacular!

Are you lurking in the closet among other clothes I own?

I gently touch your shoulder—a brief flash, then you’re gone

The concert souvenir shirts we outgrew

The obligation gifts we always knew

… were wrapped in haste

Thick cotton plaids lost lumberjacks would covet

That college T tossed out, but how we loved it

… still, such a waste

You promised transformation, but what else did you require

The full ensemble led us toward transcendence or desire

(Attire of another age, accessories all the rage)

Bell-bottom flares that took flight as we walked

Embroidered jeans so tight that people talked

… of nothing else

Those bomber jackets earthbound boomers froze in

Those leather wristlets grunge guitar gods posed in

… with death’s head belts

You folded in your fabric everyone I used to be

Now that you’re gone, I realize I’m left with only me

But if I run across you in some thrift shop bargain rack

Or rummaging recycling bins, what else would you bring back?

Who else will you bring back?

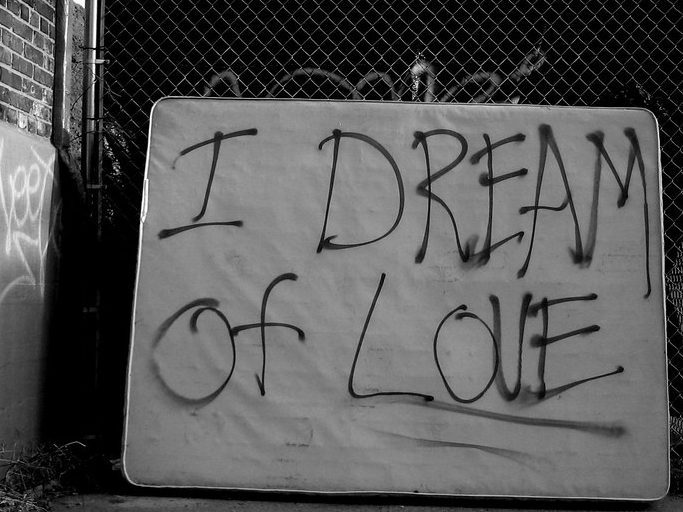

Some nights I see you in my dreams of places far away

I’m wearing you as if I haven’t aged a single day

Shirts of the distant past, shirts of the distant past

*****

Ned Balbo writes in Rattle #85, Fall 2024 (where you can hear the song performed): “I’ve played guitar since I was 5, keyboards since I was 13, and ukulele since I was 42, but my time as a ‘professional’ musician—someone paid to play—is scattershot and humble. Ice rinks, a Knights of Columbus Hall, a campers’ convention in Yaphank, a crowd of disco-loving retirees at Montauk’s Atlantic Terrace Motel, company picnics, school dances, private parties, and more—these were where I played guitar, sang, and devised versions of the Beatles, Bowie, et al. in two Long Island cover bands. The Crows’ Nest or Tiffany’s Wine-and-Cheese Café hosted noise-filled solo acoustic gigs, with more receptive listeners for original songs and covers of Elvis Costello or Eno at my undergrad college’s coffeehouse. More recently, I’ve written lyrics to Mark Osteen’s preexisting jazz scores (look for the Cold Spring Jazz Quartet on Spotify, Amazon, CDBaby, and elsewhere) and returned to solo songwriting and recording with ‘ned’s demos’ at Bandcamp. As a relic from the age when lyrics were sometimes scrutinized with poetry’s intensity, I listen closely to the sonics of language, whether sung or spoken, and look up to lyricists whose words come alive both aloud and on the page.”

Balbo: Robin, thanks for posting ‘Shirts from the Distant Past’, my little song-poem hybrid. I’ll be happy to answer any questions you have.

Editor: For myself, I see a continuum from womb heartbeat to dance to music to song to formal verse. I would love to have any additional comments on the subject in general, or on the creation of this poem in particular, related to these elements.

Balbo: I love what you’re saying about womb, heartbeat, and dance. A formative text for me is Donald Hall’s essay on poetic form’s psychic origins, ‘Goatfoot, Milktongue, Twinbird‘. You probably know it. Hall proposes three metaphors for poetry’s deepest sources: Goatfoot, the impulse toward dance, rhythm, movement; Milktongue, the pure pleasure of language, the texture of words when spoken; and Twinbird, our desire for form, symmetry, wholeness, which is complicated and energized by the contradictions it contains and reconciles. To me, Hall’s terms just sound like different ways of envisioning exactly what you’re talking about. They apply as much to song as they do to verse. The meter varies by stanza or section: iambic heptameter (seven iambs) in the couplet verses—not so different, after all, from the tetrameter to trimeter shifts we find in many ballads. The “shirts” title refrain, which doesn’t appear in print till the last line, are two trimeter phrases. It was fun to find surprising rhymes to hold the whole song together.

Editor: Regarding ‘Shirts’, quite apart from the charming idea, I like the work that has gone into the metre, rhyme, idiosyncratic structure.

Balbo: Thank you. I wrote and sung ‘Shirts’ as a poetic song lyric—one that could be read and enjoyed but, ideally, would be heard. I view its structure as that of a call-and-response song in traditional format. (In rock, for example, I think of George Harrison’s ‘Taxman’ with John and Paul harmonizing “Taxman, Mr. Wilson, Taxman, Mr. Heath” in answer George’s lead vocal.) In ‘Shirts’, the call-and-response comes from using the title as a refrain: it explains who the “you” is in each verse (when you hear it, anyway—I cut it from the visual text for fear it would seem repetitious without the music). Sometimes the title refrain answers a statement in the verse: “I gently touch your shoulder—a brief flash, then you’re gone” sounds like I might be talking (or singing) about a person, but it turns out to be those long-lost shirts—a playful fake-out.

Then there are the brief call-and-responses of the bridge sections which comment on the previous line or complete an unfinished thought: “Those V-neck disco shirts that dance no more…spectacular!” or “Embroidered jeans so tight that people talked…of nothing else.” They’re in iambic pentameter, with the second and fourth changing to heptameter if we count the two extra beats (set off on their own line) answering them.

The so-called “middle 8” (usually eight bars used to break up the verse-chorus/verse-chorus model) is delayed till just before the end: “You folded in your fabric everyone I used to be, etc.” That’s meant to set up the payoff: it’s not the shirts but our lost selves— along with loved ones, lost ones, everyone—we’re missing or mourning. But writing or singing about shirts—clothing that shapes and defines us—makes the lyric less depressing, leavens it with wit (I hope) so that what’s more poignant comes at the very end where more dramatic music can counterbalance the mood—the contradictions reconciled, as Donald Hall might have put it.

Of course, the very end is quieter – wistful again.

As I mentioned in Rattle (thanks again to Tim Green for giving both words and music a home), I grew up in the era when lyrics were often analyzed as seriously as poetry (and not just by undergraduates in long-ago dorm rooms under black light posters). Whether I’m writing poetry or songs, I listen closely to the different ways words sound—what works when sung doesn’t always work as well when spoken or encountered on the page—so when I do write lyrics, I try to make them both readable and singable.

Poems and song lyrics operate differently, but there’s lots of overlap between them. I wanted ‘Shirts’ to operate on both levels, even if it tilts more toward song lyric than poem.

*****

Ned Balbo’s six books include The Cylburn Touch-Me-Nots (New Criterion Prize), 3 Nights of the Perseids (Richard Wilbur Award), Lives of the Sleepers (Ernest Sandeen Prize), and The Trials of Edgar Poe and Other Poems (Donald Justice Prize and the Poets’ Prize). He’s received grants or fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts (translation), the Maryland Arts Council, and the Mid Atlantic Arts Foundation. Balbo has taught at Iowa State University’s MFA program in creative writing and environment and, recently, the Frost Farm and West Chester University poetry conferences. His work appears in Contemporary Catholic Poetry (Paraclete Press), with new poems out or forthcoming in Able Muse, The Common, Interim, Notre Dame Review, and elsewhere. He is married to poet and essayist Jane Satterfield.

Literary: https://nedbalbo.com

Music: https://nedsdemos.bandcamp.com

‘Fluent Phrases in a Silver Chain: on finding poetry in song and song in poetry’ (essay in Literary Matters): https://www.literarymatters.org/14-2-fluent-phrases-in-a-silver-chain-on-finding-poetry-in-song-and-song-in-poetry/

Latest book: The Cylburn Touch-Me-Nots (Criterion Books): https://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/1641770821/thenewcriterio

Photo: “December 22-31, 2009” by osseous is licensed under CC BY 2.0.