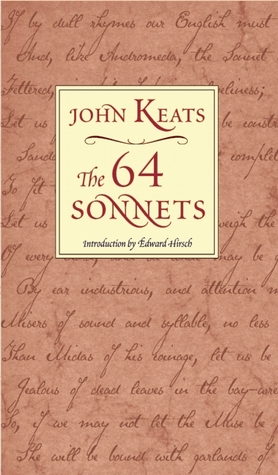

The 64 extant sonnets of John Keats make for a very interesting read for anyone interested in formal verse. Not only do we have the poet developing his skills and  expression in the last five years of his short life (he was 18 when he wrote his first sonnet, and died at 23), but he consciously experimented with the form, outlining in his letters the shortcomings that he saw in the Petrarchan and Shakespearean versions while he looked for a better structure.

expression in the last five years of his short life (he was 18 when he wrote his first sonnet, and died at 23), but he consciously experimented with the form, outlining in his letters the shortcomings that he saw in the Petrarchan and Shakespearean versions while he looked for a better structure.

This collection has a useful but insufficient introduction by Edward Hirsch and incompetent notes by Gary Hawkins. Hirsch writes of the development of Keats’ themes, but fails to tie the poems into the details of his life. I suggest reading at least the Wikipedia entry on Keats to get a fuller sense of what was going on in his mind, his life, his environment.

The notes by Hawkins appear to have been thrown together without either care or insight. There is a facing page of three or four comments for each poem, and there is a further note on the rhyme scheme in an appendix at the back. The appendix catches four of the lengthened lines (6 or even 7 feet in a line) but misses three of them; and notes one of the shortened lines but misses another. Worse, the analysis of the rhyme scheme for the technically most interesting sonnet (“If by dull rhymes our English must be chain’d”) fails to understand the structure Keats was creating, despite quoting his comments in the letter containing the poem.

Hawkins gives the structure as

abc ad (d) c abc dede (tercets, quatrain)

This is wrong on so many levels… First, the fifth line’s rhyme is b, not d. Second, there is no quatrain at all. Third, Keats has shown how to analyze the sonnet – which is a single sentence – by breaking it into tercets with the use of semicolons to clarify the structure of his thought. Its structure is

abc; abd; cab; cde; de.

That this doesn’t fit into Hawkins’ categories of Petrarchan and Shakespearean sonnets is precisely the point Keats makes in his letter (“I have been endeavouring to discover a better sonnet stanza than we have”) as well as in the sonnet itself (“Let us find out, if we must be constrain’d, / Sandals more interwoven and complete / To fit the naked foot of Poesy;”)

Hawkins also makes errors of fact and interpretation in the notes facing the sonnets themselves. The very first sonnet, written in 1814, references “the triple kingdom” which Hawkins explains as “Great Britain, composed of England, Scotland and Wales.” Wrong. With the Act of Union of 1801 the three kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland were united, as represented by the simultaneous creation of the Union Jack with its combination of the crosses of the three flags. Wales was not a kingdom but a principality, and its flag never figured in the larger national flags.

In the sonnet “How many bards gild the lapses of time!”, Keats writes “A few of them have ever been the food / Of my delighted fancy.” Hawkins annotates this as “namely, the epic poets Milton and Spenser.” Oh really? How about Shakespeare, whom Keats addresses directly as “Chief Poet!” in another sonnet. And this is quite apart from sonnets addressed to Byron, Chatterton, Hunt, and Burns.

I have to smile at Hawkins’ interpretation of “artless daughters”:

Happy is England, sweet her artless daughters;

Enough their simple loveliness for me,

Enough their whitest arms in silence clinging:

Yet do I often warmly burn to see

Beauties of deeper glance, and hear their singing,

And float with them about the summer waters.

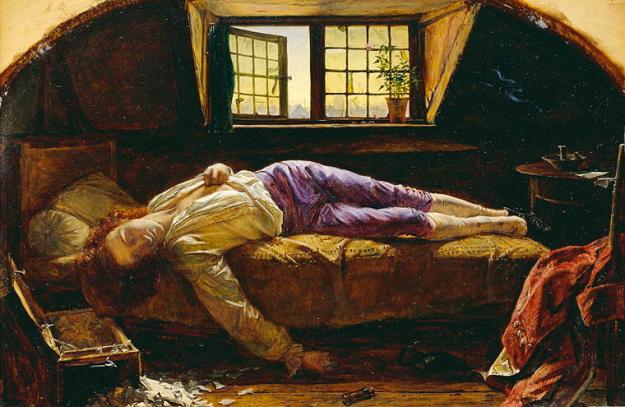

Hawkins interprets the “artless daughters” as “Scotland and Wales”. Oh come on! Keats could fall in love at a girl’s glance, at a stranger pulling off a glove. I don’t think he meant Scotland and Wales – he meant girls, classic “English rose” girls, and contrasted them with what he might find in the Mediterranean. Where he went, and died.

Few of the sonnets are near as memorable as “On first looking into Chapman’s Homer” or “When I have fears that I may cease to be”, but they are all readable and rereadable, and to have them as this collection is a treat.

That said, most of Hopkins’ poetry is uninteresting in content except to a religious person, or to a person interested in poetic technique and the elasticity of the English language. His ‘sprung rhythm’ work and his use of alliteration and assonance draw on Anglo-Saxon rather than Norman French roots, though he frequently uses the sonnet and other rigid structures. His phrasing of his thoughts, however, is idiosyncratic and often dense to the point of unreadability.

That said, most of Hopkins’ poetry is uninteresting in content except to a religious person, or to a person interested in poetic technique and the elasticity of the English language. His ‘sprung rhythm’ work and his use of alliteration and assonance draw on Anglo-Saxon rather than Norman French roots, though he frequently uses the sonnet and other rigid structures. His phrasing of his thoughts, however, is idiosyncratic and often dense to the point of unreadability.