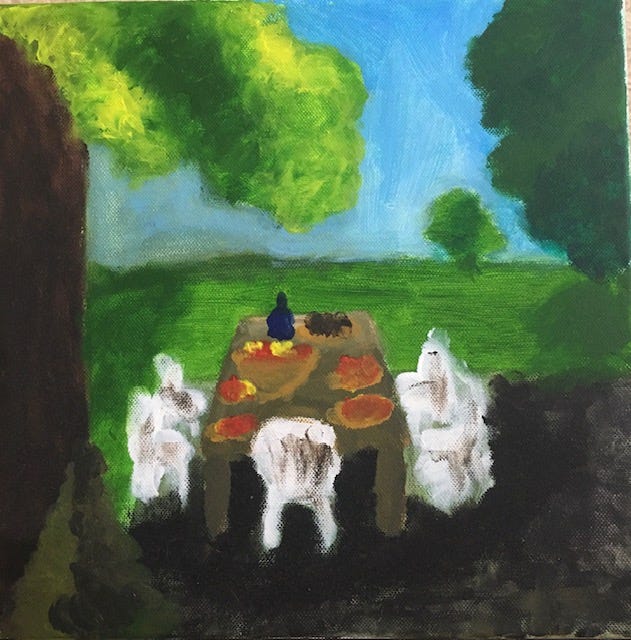

It was the ravage of the scene that shocked:

the concrete torn by trees and ragged grass,

red guts of fuel pumps over splintered glass,

the wreckage clawed by climbing vines and mocked

by moth and rust. There in concentric rings

obscene graffiti spelled out every sin.

(The smell of something even worse within.)

It’s like we saw into the death of things.

But what about the ruins I can claim?

What of the loves that I have let decay,

the hand withheld, the times I didn’t say

I’m sorry, didn’t pray for you by name?

We leave shell stations, call them what you will.

Neglect is the unkindest way to kill.

*****

Kelly Scott Franklin writes: “Originally sparked by an ekphrastic prompt over at Rattle Magazine (declined; first published in Ekstasis Magazine), this poem was ALSO inspired by a real abandoned gas station somewhere along the highway through the mountains on the way to Knoxville, TN. But I think it had been cooking in me for a while. I took a trip across the American heartland, from Southern Michigan to Central Kansas, and was absolutely depressed by the neglect and decrepitude. I stopped at a rest stop to use the restroom somewhere along the way. The restroom had a sign that said, “We take pride in the quality of our service. If anything in this restroom is not up to your satisfaction, please contact the management.” I looked around the restroom and there was garbage everywhere. Everywhere. It’s like people have stopped living the basic human things. The poem was also inspired by my troubled relationship with my late mother.”

Kelly Scott Franklin lives in Michigan with his wife and daughters. He teaches American Literature and the Great Books at Hillsdale College. His poems and translations have appeared in AbleMuse Review, Literary Matters, Driftwood Literary Magazine, Iowa City Poetry in Public, National Review, Thimble Literary Magazine, Ekstasis, and elsewhere. His essays and reviews can be found in Commonweal, The Wall Street Journal, The New Criterion, Local Culture, and elsewhere.

https://www.hillsdale.edu/faculty/kelly-scott-franklin/

“Abandoned Gas Station, 2013” by Genial23 is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.