I heard the squelch of death again –

or was it just a neuron firing

deep within my boggy brain,

or possibly a cell expiring

down amongst a mucus mess?

It could have been my heart perspiring

(that may be a thing I guess)

or, deep down in the adipose,

the squealing of a fat-lump pressed

to serve as fuel, and I suppose

it might have been a small mutation –

‘Pop!’ (we get a lot of those),

a bronchiole’s sharp inhalation,

‘Hiss!’ a membrane’s gooey breath,

a bile-duct’s bitter salivation…

Probably, it wasn’t death.

Nina Parmenter writes: “I had such a good time writing this poem. For a start, I got to have a lovely little geek-out researching a few anatomical details. I do like writing poems which require a little research, and biology seems to be a favourite subject at the moment. With bronchioles and bile ducts firmly in place, I granted myself permission to fill the rest of the poem with as many gooey, yucky words and noises as I pleased. And who wouldn’t enjoy doing that?

To compound the pleasure, I wrote the poem in terza rima form – such an elegant, flowing puzzle of a form, and one of my favourites to write in.

Honestly, this is one of those poems that I wish had taken me longer, because I didn’t want the (slightly dark) fun to stop.”

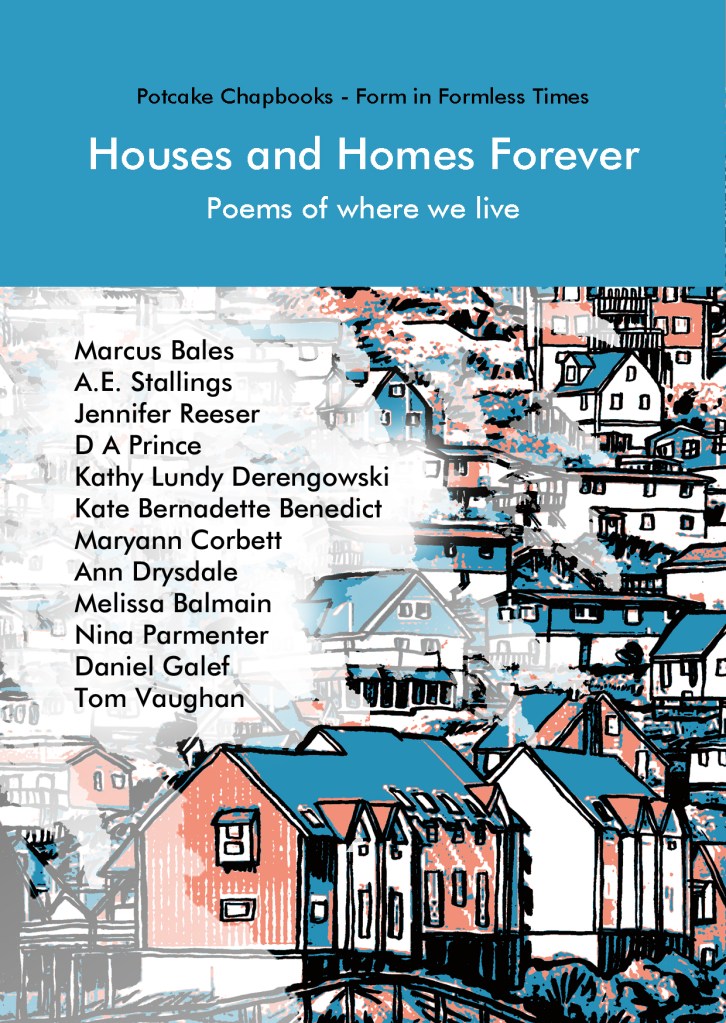

Nina Parmenter has no time to write poetry, but does it anyway. Her work has appeared in Lighten Up Online, Snakeskin, Light, The New Verse News and Ink, Sweat & Tears, as well as the newest Potcake Chapbook, ‘Houses and Homes Forever‘. Her home, work and family are in Wiltshire. Her blog can be found at http://www.itallrhymes.com. You can follow the blog on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/itallrhymes