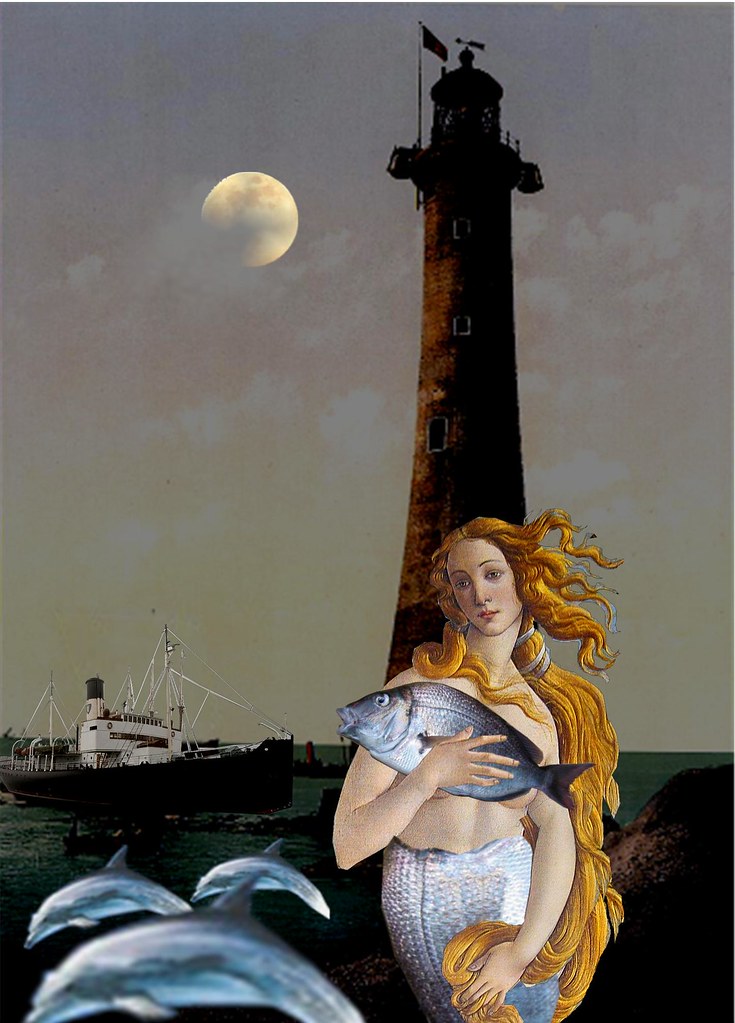

She needed constant, searching light

And some firm continent

From which to dive into the night

To find what darkness meant.

She fought the horses of the tides

And they her urgency.

She caught their lunar reins and rides

Triumphant out to sea.

And now she knows the powers of

The dark sea’s character,

And scorns the note her former love

Moans out, moans out to her.

*****

Marcus Bales writes: “Probably poets ought not tell this sort of story about their work. I found a stash of very old poems, carefully typed out on now-yellowed paper in a metal file box amid 5” Tandy floppy discs, and printed on a dot-matrix printer, a little faded, some months ago, and have started the often painful task of retyping them into my little electronic library of my work. Many of them are obviously student stuff, but this one seemed a little less studious than the rest. It brought back its context in my mind pretty clearly.

This is a very early poem, maybe sophomore year. I’d read someone’s comment that Yeats wrote about his friends as if they were characters in a Greek myth, and it had struck me as a sudden truth — to me, anyway. Nothing would do, of course, except to try the thing on my friends. Then a woman I knew gave me a copy of Adrienne Rich’s ‘Transformations’, which tells the stories of ancient myths about women, mostly, as if they had much more contemporary attitudes, and that seemed like a much better model than the Yeats tone and manner — and besides, Yeats had already done that tone and manner. So though the idea originated in Yeats, it is really Rich’s idea that I tried to follow, trying for the tone of metaphor in a contemporary voice. And Larkin was in there somewhere too, as I recall, having discovered him when asked to write a paper contrasting and comparing one of his poems to one of Wilbur’s. The Larkin was the one starting:

Sometimes you hear, fifth-hand,

As epitaph:

He chucked up everything

And just cleared off,

And that led me to many others, notably ‘The Trees’, with its amazingly unlarkinish repetition at the end.

Steal from the best has long been my motto.”

Not much is known about Marcus Bales except that he lives and works in Cleveland, Ohio, and that his work has not been published in Poetry or The New Yorker. However his ’51 Poems’ is available from Amazon. He has been published in several of the Potcake Chapbooks (‘Form in Formless Times’).

Photo: “my father was the keeper of the eddystone light” by sammydavisdog is licensed under CC BY 2.0.