Across the sea goes Attis in his ship of sleek rapidity,

To Phrygia, and its forest, which he rushes into eagerly,

The great goddess’s territory, her tree-dark sanctuary.

There he grabs a flint; he jabs and savages his genitals,

Stabs until he’s sure he’s lost the burden of virility;

His blood spills its darkness on the sacred ground surrounding him.

SHE now, never he, SHE reaches for a tambourine,

The tympanum, Cybele, that is used by your initiates,

She beats out her message on the leather of the instrument;

Up she rises, and calls out to all her followers:

My she-priests hurry, to these woods of our divinity.

Hurry all you wanderers, all great Cybele’s worshippers,

You searchers for an otherwise, you riskers and adventurers

You voyagers who’ve dared the seas that match you in your truculence,

You like me whose dream has been self-immolated genitals,

Like me detesting Venus with the utmost of ferocity,

Set free your minds with the liberty of ecstasy.

Gladden our goddess, hurry here to worship her,

Hurry to this Phrygian domain of femininity,

Hurry to the cymbals, to the gentle flute’s seductiveness,

Towards the fevered drums and the Maenads’ ululations

There we must hurry for the celebration ritual.

Attis thus addressed them; she had all the look of womanhood;

Tongues lisped lovingly and cymbals clashed resoundingly.

Attis led on frenziedly, her wild breath labouring

Free as a heifer who’s escaped the yoke of drudgery,

Weary in her lungs, she through the woods leads rhythmically

The Gallae, who are following behind her storming leadership.

They reach the home of Cybele, wearied out and staggering,

Hungry, over-stretched, exhausted by excessiveness.

Sleep commands their eyelids to slide down sluggishly

Excitement leaves their bodies; rage gives way to drowsiness.

Dawn comes. Sunlight. The golden face that radiates

Alike above the firm soil and the great sea’s turbulence,

Which drives away darkness and banishes the weariness

Even from Attis, who is gradually awakening.

(For the goddess Pasithea’s taking Somnus to her bosom now.)

Attis, pseudo-woman, is freed now from delirium

Remembers what she did before, and sees herself now lucidly,

And knows what she has lost, and now her heart weighs heavily.

It labours in her body as she turns and walks back steadfastly,

Steadfastly and sadly, heading back towards her landing-place.

Her tearful eyes look out to sea; she renders this soliloquy

Remembering her birthplace despairingly, lamentingly.

My motherland, my origin, the one place that created me,

I must shun you like a thief now, like some dishonest runaway.

Deserting you for Ida, for a bleak and chilly wilderness,

Where brute beasts lurk, fired by hunger and rapacity.

Freed now from my madness by the shock of the reality,

My eyes weep with a longing for the home that was my nourisher.

Must life be now this wilderness, with only fading memories

Of when I was a man – but I have severed that identity –

A young man, supple, and the flower of the gymnasium,

A champion of champions among the oily combatants

Who wrestled for the glory – one who won the admiration

And the friendship of so many – how my home was garlanded!

But nevermore now I’ve become Cybele’s mere serving-wench,

Now that I’m a Maenad, a half-man, whose sterility

Must sentence me to exile, to a life of pointless wandering,

Neighbour to the boar and the wild deer in its solitude.

On these wild slopes of Ida, shadowed by the peaks of Phrygia.

How I hate my rashness; my regret becomes an agony,

Her words flying upward reached the ears of a deity,

They reached the ears of Cybele, who unleashed from their harnesses

The lions of her anger, with instructions to the left-hand one:

‘Go seek out Attis, be my agent of ferocity,

Pursue him till he’s overtaken by insanity,

Make him regret attempting to escape from my supremacy,

Lash your flanks with your tail, whip up your aggressiveness

Let the place re-echo with untamed outlandish bellowing,

Toss your long red mane in anger,’ so ordered Cybele,

Loosening the brute, who charged away unstoppably,

Raging, careering, crashing through the undergrowth,

Till it reached the white shore, where the sea was opalescent,

And that is where it saw him, Attis, solitary, delicate.

The lion charged and Attis, in a terrified delirium,

Fled towards the forest, to a destiny of hopelessness,

To existence as a slave there, the property of Cybele.

Great Goddess Cybele, Lady of Dindymus,

Vent your anger, I beseech you, far from my place of residence.

May only others feel your goad to madness and to ecstasy.

*****

George Simmers writes: “I’m not normally one for explaining poems, but my Englished version of Catullus’s poem LXIII in the current Snakeskin might be fairly mystifying to anyone coming to it unprepared.

“This is a poem that is over two thousand years old, and a remarkable one. The Victorian critic W.Y. Sellar described the ‘Attis’ as the most original of all Catullus’s poems: ‘As a work of pure imagination, it is the most remarkable poetical creation in the Latin language.’

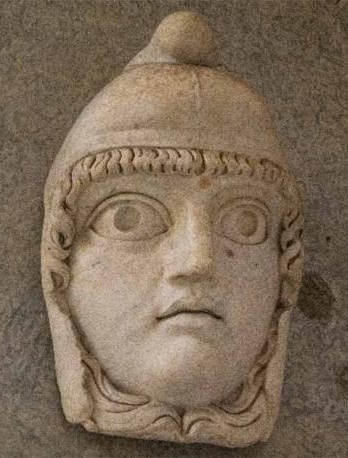

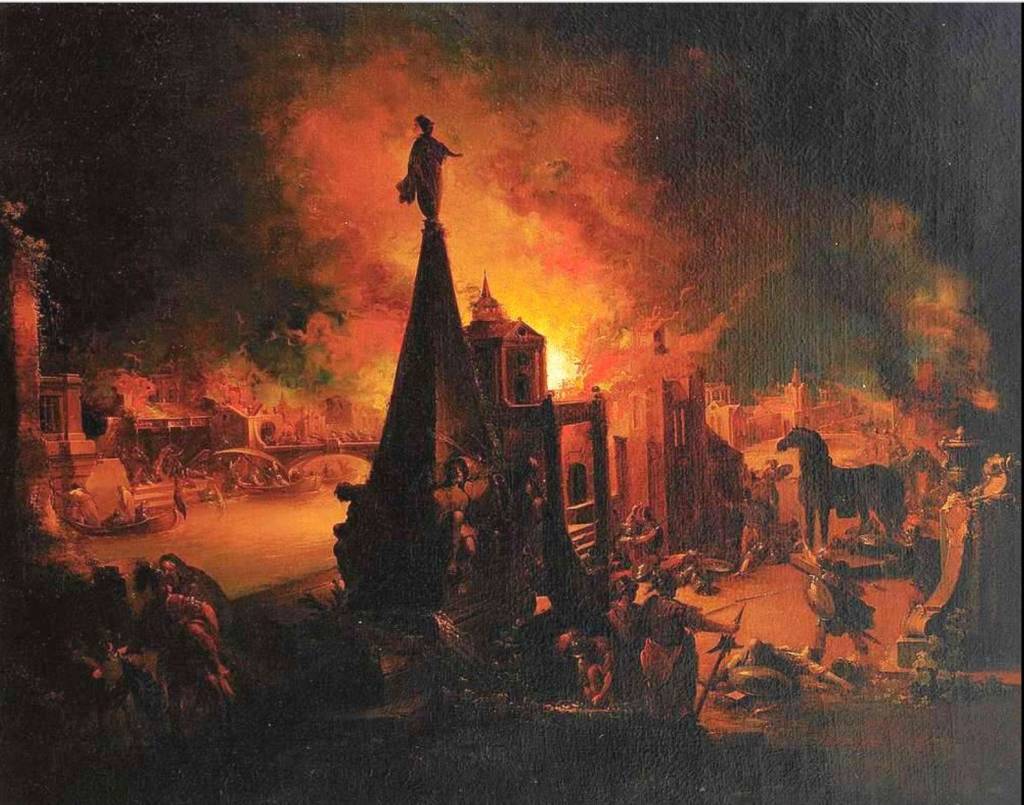

“First – to deal with a possible misconception; the Attis of this poem is not the god of that name, but a young Greek man who sails to Phrygia, the home of the Great Mother, the goddess Cybele (pronounce the C hard, like a K). In homage to her he castrates himself, to become like one of her Galli, or attendant priests. Attis celebrates jubilantly, but next morning wakes up and registers the finality of what he has done, and the irrecoverable loss of his previous identity. The poem ends with Cybele setting her lions onto him, to drive him into the forest of madness.

“Summarising the story bluntly makes it sound like a simple fable of self-harm and regret, but Catullus is not a simple poet. The poem is made more complex by the intensity of his identification both with the exultant castrated Attis, and with his later regret. Another way of looking at the poem is as a tragedy – Attis’s desire to reshape himself is a hubris that leads to his destruction. Yet although Attis is labelled a pseudo-woman (‘notha mulier’) the reality of his desire to become a woman, and the intensity of his joy when he has liberated himself from maleness, are never in doubt. Significantly, when he later expresses regret, it is not for the loss of his sexual identity, but for his social one. It is possible to see the poem as an expression of the conflict within the poet himself, between his wayward hedonistic urges and his strict Roman ethic; he imagines an extreme case of abandoning a Roman (upright male) identity and discovering the consequences.

“The poem’s intensity is in part created by the metre – galliambic. There may be Greek precedents – scholars disagree, I think – but this poem has no known fore-runner in Latin verse. It seems to be based on the rhythms of the Galli’s ceremonial music (at the Roman Megalesian festivals, presumably, where the Great Mother was celebrated, by priests carrying tambourines and castrating-knives). It is an insistent, forward-driving metre, with a unique line ending, a pattering of three short syllables. English versification is different from Roman, and direct imitation of the galliambic metre in English does not work (although Tennyson had a go in his poem Boadicea). I have tried to find an equivalent that produces a similar forward-driving rhythm. It is based on a line of two halves; before the caesura I have allowed myself some freedom, to avoid predictability, but the second half of every line hammers with dactyls, always ending with a three-syllable word or phrase. This is the best solution I’ve found to the poem’s challenge. I’ve looked at various free-verse translations, but they all seem rather slack, lacking the energy of the original. Translations into blank verse or heroic couplets make the poem too staid. The prosody of the original was unique, controlled, purposeful, and a translation needs to be equally unexpected and distinctive.

“I suspect that my version may work better spoken aloud than on the page – but then I’m attracted to T.J. Wiseman’s theory that the original poem was originally written for performance (perhaps as accompaniment to a dance, perhaps at a Megalesian festival). Elena Theodorakopoulos agrees, and in a rather good essay available on the Internet, has written:

“I am convinced that the poem must have been written with performance at or around the Megalesia in mind. My suggestion is that it was written for one of the gatherings patrician families held at their homes during the Megalesia [….] It makes sense to imagine the poem performed at such an event: the thrill of the violence and the orgiastic frenzy, the mystery of who exactly Attis was, and the sexual ambivalence of the performance, would all have provided the perfect ambience for such a gathering. And when the final lines are spoken, asking the great goddess to visit others with her fury and to keep away from the speaker’s house (domus), they are spoken by the poet himself, whose identification with Attis’ frenzy during the reading must help to appease the goddess and to keep the noble domus in which the performance has taken place safe from harm.

“Catullus LXIII is a poem full of subtleties and mysteries (I keep on finding new things in it, and new ways to tweak my version,and you can expect the translation in Snakeskin to be updated from time to time). Like most readers I was first attracted to Catullus by his short poems of love and hate. I am gradually discovering that there was so much more to him. I’m now looking at poem 64…”

*****

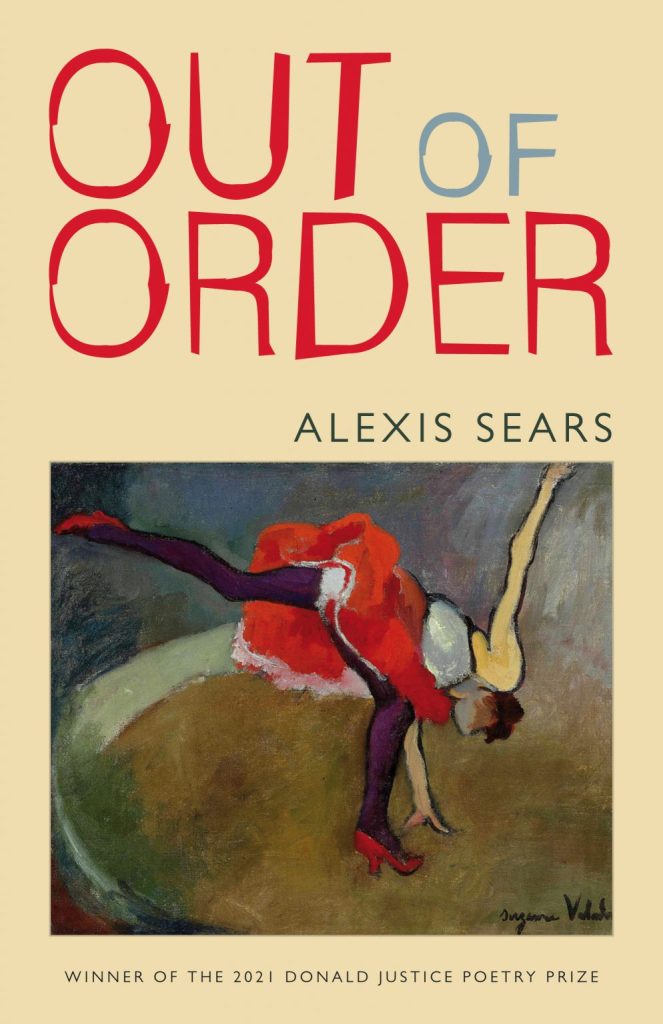

George Simmers used to be a teacher; now he spends much of his time researching literature written during and after the First World War. He has edited Snakeskin since 1995. It is probably the oldest-established poetry zine on the Internet. His work appears in several Potcake Chapbooks, and his recent diverse collection is ‘Old and Bookish’. ‘Catullus LXIII’ is from Snakeskin 320, and the explanation is from the Snakeskin blog.

Photo: from Snakeskin 320 (August/September 2024)