Jumbled in the common box

Of their dark stupidity,

Orchid, swan, and Caesar lie;

Time that tires of everyone

Has corroded all the locks,

Thrown away the key for fun.

In its cleft the torrent mocks

Prophets who in days gone by

Made a profit on each cry,

Persona grata now with none;

And a jackass language shocks

Poets who can only pun.

Silence settles on the clocks;

Nursing mothers point a sly

Index finger at the sky,

Crimson with the setting sun;

In the valley of the fox

Gleams the barrel of a gun.

Once we could have made the docks,

Now it is too late to fly;

Once too often you and I

Did what we should not have done;

Round the rampant rugged rocks

Rude and ragged rascals run.

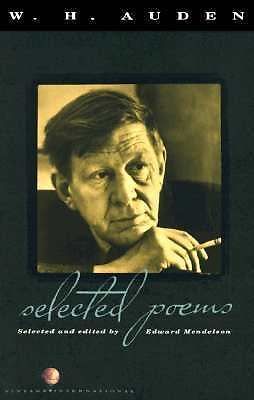

In January 1941, W.H. Auden had been living in New York for nearly two years. The Second World War had started, but not yet in the US. Auden had fallen in love with Chester Kallman who was now turning 20 and was too young to want to be sexually faithful; Auden had also returned from atheism to the existential Christianity that is common in the Anglican/Episcopalian church. It was a period of change, backgrounded by the widening war.

Regarding the poem from this time, I choose to imagine Auden rambling, reminiscing, muttering to himself: “Around the rugged rocks the ragged rascal ran… Nice metre as well as alliteration and, for people with difficulty pronouncing their Rs, a twuly tewwible tongue-twister. Rhythmic, memorable. Nonsense; not meaningful, but not meaningless; nonsense and nursery rhymes are right on the border. And it splits in two, you could easily rhyme it: rocks, box, blocks, brocks, cocks, cox, clocks, crocks… ran, Ann, ban, bran, can, clan, cran… or easy to change to run, or runs. A lot of rhymes, anyway. Run them out, see what transpires.

“Once we could have made the docks, / Now it is too late to fly; that adds another rhyme, not a problem, maybe a 6-line stanza. Once too often you and I / Did what we should not have done; and into the last two lines, have to fill them out a bit to maintain the metre, keep the alliteration of course: Round the rampant rugged rocks / Rude and ragged rascals run… So that’s all right, that would make an ending.

“Then of course we can have more stanzas leading up to it. Flick a bit of paint at the canvas, see what sort of patterns we can find to elaborate on. Time, decay, trepidation, warnings… out come the words and images around the rhymes, and suddenly it’s all as evocative and semi-coherent as a reading of tarot or yarrow or horoscope. Hm, tarot or yarrow, I hadn’t noticed that before, wonder if I can use that somewhere else…”

(Remember, this is a fantasy analysis, presupposing the poem to have been written with full skill to capture both rhymes and a mood, but without any serious intent beyond that. For a completely different intellectual analysis, you can always try this…)

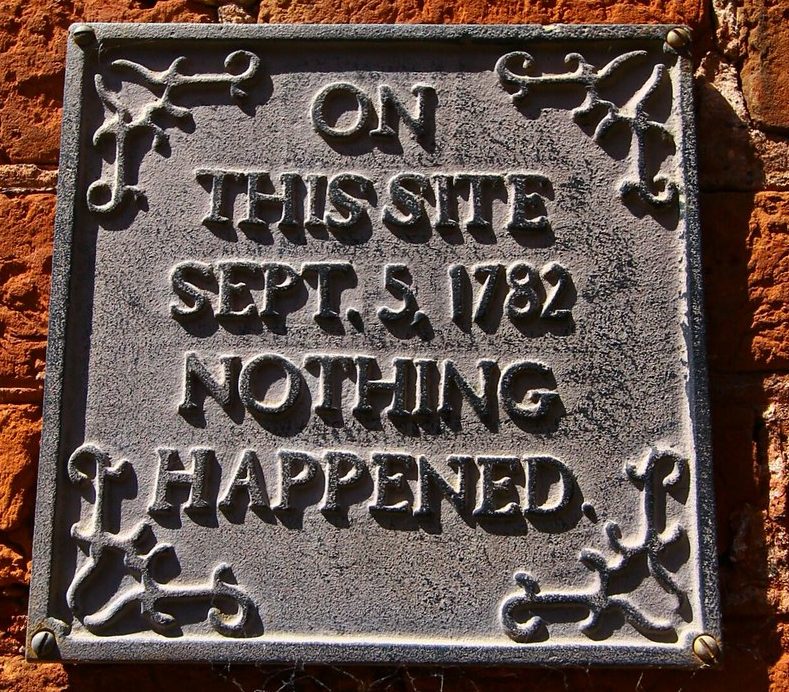

Photo: “Jumble Box” by .daydreamer. is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0