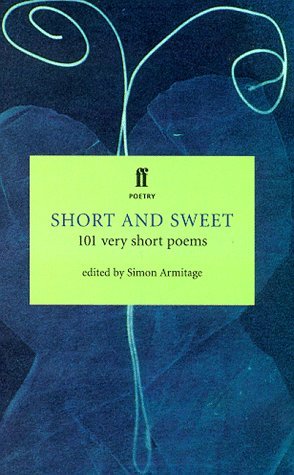

One of a series of short poetry collections that Faber produced in the 1990s, this one features a good introduction by the anthologist (and poet well-known in the UK) Simon Armitage, discussing and justifying the short poem:

“The short poem, at its best, brings about an almost instantaneous surge of both understanding and sensation unavailable elsewhere; its effect should not be underestimated and its design not confused with convenience.”

Of course I love them, they are my children.

This is my daughter and this my son.

And this is my life I give them to please them.

It has never been used. Keep it safe. Pass it on.

– The Mother, by Anne Stevenson

Armitage defines the short poem as no more than 13 lines, thereby ruling out the sonnet as something more than short. Other people define it in other ways: the Shot Glass Journal publishes anything up to 16 lines under its “Brevity is the soul of wit” motto, while another of my favourite collections of verse defines the short poem as ‘Eight Lines or Less’. There is no agreed definition of “short poem”. And as Armitage shows, in 13 lines you can still cover a lot of ground.

She lay a long time as he found her,

Half on her side, askew, her cheek pressed to the floor.

He sat at the table there and watched,

His mind sometimes all over the place,

And then asking over and over

If she were dead: ‘Are you dead, Poll, are you dead?’

For these hours, each one dressed in its figure

On the mantelpiece, love sits with him.

Habit, mutuality, sweetheartedness,

Drop through his body,

And he is not able now to touch her–

A bar of daylight, no more than

Across a table, flows between them.

– As He Found Her, by Jeffrey Wainwright

Some of the poems in the collection were new to me, including both the above. Some of the poems are extremely well-known but always a joy to read: Yeats’ ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’, William Carlos Williams’ ‘This is Just to Say’. And others hover half-known:

Where is the grave of Sir Arthur O’Kellyn?

Where may the grave of that good man be?

By the side of a spring, on the breast of Helvellyn,

Under the twigs of a young birch tree!

The oak that in summer was sweet to hear,

And rustled its leaves in the fall of the year,

And whistled and roared in the winter alone,

Is gone, — and the birch in its stead is grown. —

The Knight’s bones are dust,

And his good sword is rust; —

His soul is with the saints, I trust.

– The Knight’s Tomb, by Coleridge

Starting off with the 13-liners, the poems get shorter and shorter as you read on, but without losing their punch–perhaps, as the introduction suggests, condensing their power.

Shakespearean fish swam the sea, far away from land;

Romantic fish swam in nets, coming to the hand;

What are all those fish that lie gasping on the strand?

– Three Movements, by Yeats

… all the way down to the final poem with no text at all, but only its title:

– On Going to Meet a Zen Master in the Kyushu Mountains and Not Finding Him, by Don Paterson.

Most but not all of the 101 poems are formal; most are originally in English, though there are a few translations: Paz, Sappho, Apollinaire, Salamun and – most surprising in its elegant translation from the Polish – this one, ‘Bodybuilders’ Contest’:

From scalp to sole, all muscles in slow motion,

The ocean of his torso drips with lotion.

The king of all is he who preens and wrestles

with sinews twisted into monstrous pretzels.

Onstage, he grapples with a grizzly bear

the deadlier for not really being there.

Three unseen panthers are in turn laid low,

each with one smoothly choreographed blow.

He grunts while showing his poses and paces.

His back alone has twenty different faces.

The mammoth fist he raises as he wins

is tribute to the force of vitamins.

– Bodybuilders’ Contest, by Wislawa Szymborska.

Altogether an excellent and well-rounded collection.